Inhaltsangabe

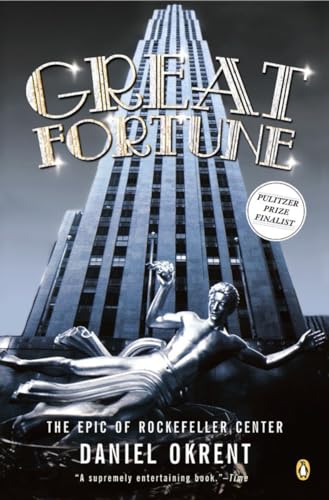

In this hugely appealing book, a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize, acclaimed author and journalist Daniel Okrent weaves together themes of money, politics, art, architecture, business, and society to tell the story of the majestic suite of buildings that came to dominate the heart of midtown Manhattan and with it, for a time, the heart of the world. At the center of Okrent's riveting story are four remarkable individuals: tycoon John D. Rockefeller, his ambitious son Nelson Rockefeller, real estate genius John R. Todd, and visionary skyscraper architect Raymond Hood. In the tradition of David McCullough's The Great Bridge, Ron Chernow's Titan, and Robert Caro's The Power Broker, Great Fortune is a stunning tribute to an American landmark that captures the heart and spirit of New York at its apotheosis.

Die Inhaltsangabe kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Über die Autorin bzw. den Autor

Daniel Okrent is a prizewinning journalist, author, and television commentator. For many years he was a senior editorial executive at Time Inc. In 2003 he was appointed the first Public Editor of the New York Times.

Auszug. © Genehmigter Nachdruck. Alle Rechte vorbehalten.

A NOTE TO THE READER

Places: I wish the names of buildings were as simple as, say, designing, erecting, and occupying a group of remarkable structures in the heart of America’s largest city in the middle of the Great Depression. In most instances my proper nouns are the ones in use during the periods I’m writing about. Therefore, at different points in this book different names are used to describe one thing: Metropolitan Square, Radio City, Rockefeller City, Rockefeller Center; looking back from today, it’s always Rockefeller Center. For individual buildings I’ve generally used the names they were known by when built—thus, the building now called 1270 Avenue of the Americas is referred to here as the RKO Building; the Time & Life Building I refer to is the original version, south of the skating rink, and not the current one on Sixth Avenue. (The illustration on pages viii–ix should clarify any nomenclatural murkiness.) By “Rockefeller Center” itself, I mean those buildings completed before World War II. The two later buildings in the original style (Sinclair and Esso) and all those across Sixth Avenue, from 46th Street to 51st Street, are formally part of Rockefeller Center, but not of the concept that became Rockefeller Center.

Numbers: Dates of buildings vary by source—some authorities use the date when construction begins, some the date when it ends. When in doubt, I’ve gone with the dates provided by Norval White and Elliot Willensky in their indispensable AIA Guide to New York City. The height of buildings, in feet as well as in stories, is often the concoction of developers and their publicists, who like to count rooftop air vents, water tanks, radio antennae, and anything else that can stretch the “official” number. I’ve generally allowed them their fun, except where it’s material, as in the case of the sixty-six- (or maybe sixty-seven-, but not remotely seventy-) story RCA Building. Same with quantity of buildings: Rockefeller Center management has always counted the six-story eastern appendages of the International Building as separate structures, but the whole thing is clearly one building, and I count it as such.

People: The only nomenclatural issue here has to do with the family at the book’s heart, the Rockefellers. The three men bearing the name John Davison Rockefeller are here referred to in two instances by the names by which they are known to the family archivists—Senior and Junior. The third, depending on context, is either Johnny or John.

Some readers may think a more material issue concerning people has to do with gender: save for a very few lesser characters, this saga has an all-male cast. This is a reflection of the era, and not of any authorial bias.

Finally, a comment on memory: Interviews are great for color and for a sense of personality. But even those conducted much closer to the events described here—those compiled by the Columbia University Oral History Project, for instance, or by the excellent architectural historian Carol Herselle Krinsky—are flawed by that most unreliable of research tools, memory. Contemporary documents, however, are precise. When I’ve encountered a conflict of facts, either I point it out in context or go with the one that seems to me, after six years’ immersion in this project, to be accurate. In a jump ball, the document almost always wins.

—D. O.

New York, March 2003

PROLOGUE

MAY 21, 1928

All the men entering the gleaming marble hall of the Metropolitan Club had arrived at Fifth Avenue and 60th Street on the wings of their wealth. The guest list was a roll call of New York’s richest: corporate titans Marshall Field, Clarence Mackay, and Walter P. Chrysler; Wall Street operators Jules S. Bache, Bernard Baruch, and Thomas Lamont; various Lehmans and Whitneys, Guggenheims and Warburgs, men whose very surnames provided all the definition they needed. Financier Otto Kahn was there, for Otto Kahn was ubiquitous in New York if opera was on the agenda, as it was on this balmy night. But an interest in Verdi or Wagner was not the primary qualifier for inclusion on the invitation list. According to a young architect named Robert O’Connor, whose father-in-law was scheduled to be the featured speaker, the evening’s host had simply invited everyone he knew who had more than ten million dollars.

Not all of them belonged to the Metropolitan Club, but there was no better venue for a convocation of the New York plutocracy. J. P. Morgan had founded the Metropolitan in 1891, after his friend John King, president of the Erie Railroad, was blackballed by the Union Club (Morgan said it was an act of spite; others insisted that certain members were offended by King’s dreadful table manners). Morgan’s stature had guaranteed a membership distinguished not solely by heredity or by financial success but by an unprecedented confluence of both. By 1928 the Metropolitan membership included two Vanderbilts, three Mellons, five Du Ponts, and six Roosevelts. It also included three men who were parties of interest to the evening’s proceedings. One was the host, an aristocrat named R. Fulton Cutting, known to some as “the first citizen of New York.” Another was Nicholas Murray Butler, president of Columbia University and a member of the Metropolitan’s board of governors, who knew that the future of his institution was to a large degree dependent on the evening’s outcome. The third was Ivy Ledbetter Lee, a preacher’s son from Georgia representing the man who, even in his absence, was the lead player in the evening’s drama.

No one expected John D. Rockefeller Jr. to attend the meeting at the Metropolitan Club that Monday night, and he didn’t disappoint. He wasn’t much of a clubman, generally preferring to spend his evenings at home in his nine-story mansion on West 54th Street; just the night before, he and his wife, Abby, had welcomed to a typical “family supper” another Ivy Lee client, Colonel Charles Lindbergh—“a simple, unostentatious, cleancut, charming fellow,” Rockefeller wrote. Rockefeller usually sought to insulate himself from the endless entreaties for access to the family treasury, and the Metropolitan Club event was clearly in that category. He got a lot of invitations of this kind, and almost always chose to deputize one of his associates to serve as a sort of scout.

Oddly, in this instance the scout—Lee—was collaborating with the supplicants. Odder still was the shadow play that was the evening’s presentation, offered ostensibly for the benefit of the assembled guests but mostly for the man who wasn’t there. The speaker was Benjamin Wistar Morris, an architect of middling accomplishment but excellent breeding. On this particular evening Morris was working for the board of the Metropolitan Opera Real Estate Company (R. Fulton Cutting, president), a group of men whose money was substantial, very old, and dearly husbanded. The elaborate clay model of an opera house and other buildings on the table in front of Morris; his impressive stereopticon slides; his reasoned, detailed, and admirably practical speech—how could anyone not be convinced of the enormous civic virtue that would arise from the development of a small plot of land in the center of a slummy midtown block?

Morris’s plan, Lee later reported to Rockefeller, would leave most of this land a plaza for the benefit of the public. “The Opera Company itself is able to finance the building of [a] new structure,” he added. Wasn’t it, Lee suggested, worth putting up the $2.5 million necessary to acquire this land from Columbia University, its improbable owner, so New York could...

„Über diesen Titel“ kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Weitere beliebte Ausgaben desselben Titels

Suchergebnisse für Great Fortune: The Epic of Rockefeller Center

Great Fortune: The Epic of Rockefeller Center

Anbieter: World of Books (was SecondSale), Montgomery, IL, USA

Zustand: Very Good. Item in very good condition! Textbooks may not include supplemental items i.e. CDs, access codes etc. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers 00079031442

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 2 verfügbar

Great Fortune: The Epic of Rockefeller Center

Anbieter: Gulf Coast Books, Cypress, TX, USA

paperback. Zustand: Fair. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers 0142001775-4-28656181

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Great Fortune: The Epic of Rockefeller Center

Anbieter: Orion Tech, Kingwood, TX, USA

paperback. Zustand: Good. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers 0142001775-3-27097063

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Great Fortune: The Epic of Rockefeller Center

Anbieter: Zoom Books East, Glendale Heights, IL, USA

Zustand: acceptable. Book is in acceptable condition and shows signs of wear. Book may also include underlining highlighting. The book can also include "From the library of" labels. May not contain miscellaneous items toys, dvds, etc. . We offer 100% money back guarantee and 24 7 customer service. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers ZEV.0142001775.A

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Great Fortune: The Epic of Rockefeller Center

Anbieter: Greenworld Books, Arlington, TX, USA

Zustand: good. Fast Free Shipping â" Good condition. It may show normal signs of use, such as light writing, highlighting, or library markings, but all pages are intact and the book is fully readable. A solid, complete copy that's ready to enjoy. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers GWV.0142001775.G

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 2 verfügbar

Great Fortune: The Epic of Rockefeller Center

Anbieter: More Than Words, Waltham, MA, USA

Zustand: Very Good. . . All orders guaranteed and ship within 24 hours. Before placing your order for please contact us for confirmation on the book's binding. Check out our other listings to add to your order for discounted shipping. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers WAL-O-2b-01760

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Great Fortune: The Epic of Rockefeller Center

Anbieter: HPB-Diamond, Dallas, TX, USA

paperback. Zustand: Very Good. Connecting readers with great books since 1972! Used books may not include companion materials, and may have some shelf wear or limited writing. We ship orders daily and Customer Service is our top priority! Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers S_451525902

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Great Fortune: The Epic of Rockefeller Center

Anbieter: HPB-Movies, Dallas, TX, USA

paperback. Zustand: Very Good. Connecting readers with great books since 1972! Used books may not include companion materials, and may have some shelf wear or limited writing. We ship orders daily and Customer Service is our top priority! Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers S_453271519

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Great Fortune : The Epic of Rockefeller Center

Anbieter: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, USA

Zustand: Very Good. Reprint. Pages intact with possible writing/highlighting. Binding strong with minor wear. Dust jackets/supplements may not be included. Stock photo provided. Product includes identifying sticker. Better World Books: Buy Books. Do Good. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers 4025422-6

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Great Fortune : The Epic of Rockefeller Center

Anbieter: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, USA

Zustand: Good. Reprint. Pages intact with minimal writing/highlighting. The binding may be loose and creased. Dust jackets/supplements are not included. Stock photo provided. Product includes identifying sticker. Better World Books: Buy Books. Do Good. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers 4025421-6

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 4 verfügbar