Inhaltsangabe

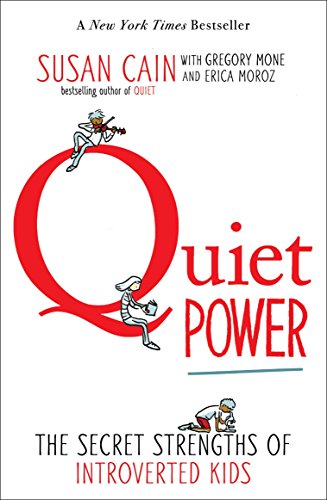

The monumental bestseller Quiet has been recast in a new edition that empowers introverted kids and teens

Susan Cain sparked a worldwide conversation when she published Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World That Can’t Stop Talking. With her inspiring book, she permanently changed the way we see introverts and the way introverts see themselves.

The original book focused on the workplace, and Susan realized that a version for and about kids was also badly needed. This book is all about kids' world—school, extracurriculars, family life, and friendship. You’ll read about actual kids who have tackled the challenges of not being extroverted and who have made a mark in their own quiet way. You’ll hear Susan Cain’s own story, and you’ll be able to make use of the tips at the end of each chapter. There’s even a guide at the end of the book for parents and teachers.

This insightful, accessible, and empowering book, illustrated with amusing comic-style art, will be eye-opening to extroverts and introverts alike.

Die Inhaltsangabe kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Über die Autorin bzw. den Autor

Susan Cain is a graduate of Princeton and Harvard Law School. She worked as a corporate lawyer and then a negotiations consultant before deciding to write Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World That Can't Stop Talking. That book became a phenomenon, translated into more than 35 languages and on the New York Times bestseller list for several years. She lives on the banks of the Hudson River with her husband and two sons.

Read more about her, and join the Quiet Revolution community, at Quietrev.com.

Auszug. © Genehmigter Nachdruck. Alle Rechte vorbehalten.

Chapter One

Quiet in the Cafeteria

When I was nine years old, I convinced my parents to let me go to summer camp for eight weeks. My parents were skeptical, but I couldn’t wait to get there. I’d read lots of novels set at summer camps on wooded lakes, and it sounded like so much fun.

Before I left, my mother helped me pack a suitcase full of shorts, sandals, swimsuits, towels, and . . . books. Lots and lots and lots of books. This made perfect sense to us; reading was a group activity in our family. At night and on weekends, my parents, siblings, and I would all sit around the living room and disappear into our novels. There wasn’t much talking. Each of us would follow our own fictional adventures, but in our way we were sharing this time together. So when my mother packed me all those novels, I pictured the same kind of experience at camp, only better. I could see myself and all my new friends in our cabin: ten girls in matching nightgowns reading together happily.

But I was in for a big surprise. Summer camp turned out to be the exact opposite of quiet time with my family. It was more like one long, raucous birthday party—and I couldn’t even phone my parents to take me home.

On the very first day of camp, our counselor gathered us together. In the name of camp spirit, she said, she would demonstrate a cheer that we were to perform every day for the rest of the summer. Pumping her arms at her sides as if she were jogging, the counselor chanted:

“R-O-W-D-I-E,

THAT’S THE WAY

WE SPELL ROWDY,

ROWDIE! ROWDIE!

LET’S GET ROWDIE!”

She finished with both her hands up, palms out, and a huge smile on her face.

Okay, this was not what I was expecting. I was already excited to be at camp—why the need to be so outwardly rowdy? (And why did we have to spell this word incorrectly?!) I wasn’t sure what to think. Gamely I performed the cheer—and then found some downtime to pull out one of my books and start reading.

Later that week, though, the coolest girl in the bunk asked me why I was always reading and why I was so “mellow”—mellow being the opposite of R-O-W-D-I-E. I looked down at the book in my hand, then around the bunk. No one else was sitting by herself, reading. They were all laughing and playing hand games, or running around in the grass outside with kids from other bunks. So I closed my book and put it away, along with all the others, in my suitcase. I felt guilty as I tucked the books under my bed, as if they needed me and I was letting them down.

For the rest of the summer, I shouted out the ROWDIE cheer with as much enthusiasm as I could muster. Every day I pumped my arms and smiled wide, doing my best approximation of a lively, gregarious camper. And when camp was over and I finally reunited with my books, something felt different. It felt as if, at school and even with my friends, that pressure to be rowdy still loomed large.

In elementary school, I’d known everyone since kindergarten. I knew I was shy deep down, but I felt very comfortable and had even starred in the school play one year. Everything changed in middle school, though, when I switched to a new school system where I didn’t know anyone. I was the new kid in a sea of chattering strangers. My mom would drive me to school because being on a bus with dozens of other kids was too overwhelming. The doors to the school stayed locked until the first bell, and when I arrived early I’d have to wait outside in the parking lot, where groups of friends huddled together. They all seemed to know one another and to feel totally at ease. For me, that parking lot was a straight-up nightmare.

Eventually, the bell would ring and we’d rush inside. The hallways were even more chaotic than the parking lot. Kids hurried in every direction, pounding down the hall like they owned the place, and groups of girls and boys traded stories and laughed secretively. I’d look up at a vaguely familiar face, wonder if I should say hello, and then move on without speaking.

But the cafeteria scene at lunchtime made the hallways look like a dream! The voices of hundreds of kids bounced off the massive cinderblock walls. The room was arranged in rows of long, skinny tables, and a laughing, gabbing clique sat at each one. Everyone split off into groups: the shiny, popular girls here, the athletic boys there, the nerdy types over to the side. I could barely think straight, let alone smile and chat in the easygoing way that everyone else seemed to manage.

Does this setting sound familiar? It’s such a common experience.

Meet Davis, a thoughtful and shy guy who found himself in a similar situation on the first day of sixth grade. As one of the few Asian American kids at a mostly white school, he was also made uncomfortably aware that other students thought he looked “different.” He was so nervous that he barely remembered to exhale until he arrived in homeroom, where everyone gradually settled down. Finally, he could just sit and think. The rest of the day went on similarly—he barely navigated his way through the crowded cafeteria, feeling relieved only during quiet moments in the classroom. By the time the bell rang at 3:30 p.m., he was exhausted. He had made it through the first day of sixth grade alive—though not without somebody throwing gum into his hair on the bus ride home.

As far as he could tell, everyone seemed thrilled to be back again the next morning. Everyone except Davis.

Introverts and the Five Senses

Things started looking up, though, in ways Davis could never have imagined on that stressful first day. I’ll tell you the rest of his story soon. In the meantime, it’s important to remember that no matter how cheerful they might have seemed, the kids at my school and at Davis’s probably weren’t all happy to be there. The first days in a new school, or even one you’ve been going to for years, can be a struggle for anyone. And as introverts, our reactivity to stimulation means that people like Davis and me really do have extra adjustments to make.

What do I mean by “reactivity to stimulation”? Well, most psychologists agree that introversion and extroversion are among the most important personality traits shaping human experience—and that this is true of people all over the world, regardless of their culture or the language they speak. This means that introversion is also one of the mostresearched personality traits. We’re learning fascinating things about it every day. We now know, for example, that introverts and extroverts generally have different nervous systems. Introverts’ nervous systems react more intensely than extroverts’ to social situations as well as to sensory experiences. Extroverts’ nervous systems don’t react as much, which means that they crave stimulation, such as brighter lights and louder sounds, to feel alive. When they’re not getting enough stimulation, they may start to feel bored and antsy. They naturally prefer a more gregarious, or chatty, style of socializing. Theyneed to be around people, and they thrive on the energy of crowds. They’re more likely to crank up speakers, chase adrenaline-pumping adventures, or thrust their hands up and volunteer to go first.

We introverts, on the other hand, react more—sometimes much, much more—to stimulating environments such as noisy school cafeterias. This means that we tend to feel most relaxed and energized when we’re in quieter settings—not necessarily alone, but often with smaller numbers of friends or family we know well.

In one study, a famous psychologist named Hans Eysenck...

„Über diesen Titel“ kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Weitere beliebte Ausgaben desselben Titels

Suchergebnisse für Quiet Power: The Secret Strengths of Introverted Kids

Quiet Power: The Secret Streng

Anbieter: World of Books (was SecondSale), Montgomery, IL, USA

Zustand: Good. Snider, Grant (illustrator). Item in good condition. Textbooks may not include supplemental items i.e. CDs, access codes etc. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers 00088743960

Quiet Power: The Secret Streng

Anbieter: World of Books (was SecondSale), Montgomery, IL, USA

Zustand: Acceptable. Snider, Grant (illustrator). Item in good condition. Textbooks may not include supplemental items i.e. CDs, access codes etc. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers 00060107882

Quiet Power: The Secret Streng

Anbieter: World of Books (was SecondSale), Montgomery, IL, USA

Zustand: Very Good. Snider, Grant (illustrator). Item in very good condition! Textbooks may not include supplemental items i.e. CDs, access codes etc. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers 00093781490

Quiet Power: The Secret Strengths of Introverted Kids

Anbieter: Dream Books Co., Denver, CO, USA

Zustand: good. Snider, Grant (illustrator). Gently used with minimal wear on the corners and cover. A few pages may contain light highlighting or writing, but the text remains fully legible. Dust jacket may be missing, and supplemental materials like CDs or codes may not be included. May be ex-library with library markings. Ships promptly! Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers DBV.0147509920.G

Quiet Power: The Secret Strengths of Introverted Kids

Anbieter: Zoom Books East, Glendale Heights, IL, USA

Zustand: acceptable. Snider, Grant (illustrator). Book is in acceptable condition and shows signs of wear. Book may also include underlining highlighting. The book can also include "From the library of" labels. May not contain miscellaneous items toys, dvds, etc. . We offer 100% money back guarantee and 24 7 customer service. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers ZEV.0147509920.A

Quiet Power: The Secret Strengths of Introverted Kids

Anbieter: Zoom Books East, Glendale Heights, IL, USA

Zustand: good. Snider, Grant (illustrator). Book is in good condition and may include underlining highlighting and minimal wear. The book can also include "From the library of" labels. May not contain miscellaneous items toys, dvds, etc. . We offer 100% money back guarantee and 24 7 customer service. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers ZEV.0147509920.G

Quiet Power: The Secret Strengths of Introverted Kids

Anbieter: Reliant Bookstore, El Dorado, KS, USA

Zustand: good. Snider, Grant (illustrator). This book is in good condition with very minimal damage. Pages may have minimal notes or highlighting. Cover image on the book may vary from photo. Ships out quickly in a secure plastic mailer. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers RDV.0147509920.G

Quiet Power: The Secret Strengths of Introverted Kids

Anbieter: Zoom Books Company, Lynden, WA, USA

Zustand: very_good. Snider, Grant (illustrator). Book is in very good condition and may include minimal underlining highlighting. The book can also include "From the library of" labels. May not contain miscellaneous items toys, dvds, etc. . We offer 100% money back guarantee and 24 7 customer service. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers ZBV.0147509920.VG

Quiet Power: The Secret Strengths of Introverted Kids

Anbieter: ZBK Books, Carlstadt, NJ, USA

Zustand: acceptable. Snider, Grant (illustrator). Fast & Free Shipping â" A well-used but reliable copy with all text fully readable. Pages and cover remain intact, though wear such as notes, highlighting, bends, or library marks may be present. Supplemental items like CDs or access codes may not be included. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers ZWV.0147509920.A

Quiet Power: The Secret Strengths of Introverted Kids

Anbieter: ZBK Books, Carlstadt, NJ, USA

Zustand: good. Snider, Grant (illustrator). Fast & Free Shipping â" Good condition with a solid cover and clean pages. Shows normal signs of use such as light wear or a few marks highlighting, but overall a well-maintained copy ready to enjoy. Supplemental items like CDs or access codes may not be included. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers ZWV.0147509920.G