Inhaltsangabe

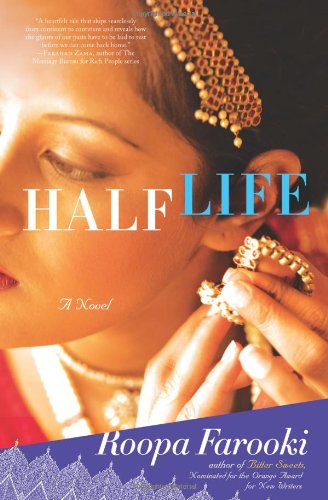

Abandoning her privileged life in England and husband of less than a year, Aruna Ahmed returns to her native Singapore, where she remembers the death of her father, her failed relationship with her best friend and a complicated psychological diagnosis she has tried to ignore.

Die Inhaltsangabe kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Über die Autorin bzw. den Autor

Roopa Farooki was born in Lahore, Pakistan, and brought up in London. She graduated from New College, Oxford in Philosophy, Politics and Economics and worked in advertising before writing fiction full time. Roopa now lives in Southeast England and Southwest France with her husband and two young sons, and teaches creative writing at the Canterbury Christ Chuch University masters' program.

Auszug. © Genehmigter Nachdruck. Alle Rechte vorbehalten.

It’s time to stop fighting, and go home. Those were the words which finally persuaded Aruna to walk out of her ground-floor Victorian flat in Bethnal Green, and keep on walking. One step at a time, one foot, and then the other, her inappropriately flimsy sandals flip-flopping on the damp east London streets; she avoids the dank, brown puddles, the foil glint of the takeaway containers glistening with the vibrant slime of sweet and sour sauce, the mottled banana skin left on the pavement like a practical joke, but otherwise walks in a straight line. One foot, and then the other. Toe to heel to toe to heel. Flip-flop. She knows exactly where she is going, and even though she could have carried everything she needs in her dressing-gown pocket – her credit card, her passport, her phone – she has taken her handbag instead, and she has paused in her escape long enough to dress in jeans, a T-shirt and even a jacket. Just for show. So that people won’t think that she is a madwoman who has walked out on her marriage and her marital home in the middle of breakfast, with her half-eaten porridge congealing in the bowl, with her tea cooling on the counter top. So that she won’t think so either. So she can turn up at the airport looking like anyone else, hand over her credit card, and run back to the city she had run away from in the first place.

It’s time to stop fighting, and go home. She hasn’t left a note. It’s not as though she is planning to kill herself, like last time. Then she had left a note, thinking it only polite, to exonerate her husband from any blame or self-reproach, to apologize and excuse herself, as though she were a schoolgirl asking to be let off gym class, instead of the rest of her life. When she had returned, having not gone through with it after all, her hair damp and reedy-smelling, as though she had simply been swimming in the Hampstead Heath Ponds instead of trying to drown herself there, the note was still on the counter. Patrick had been working late. She wasn’t sure if she had failed to end her life because she was too lazy and noncommittal – she hadn’t tried hard enough; the gentle, shallow water hadn’t tried hard enough either, it had bobbed her back up again and offered no helpful current. Perhaps, like the water, she was just too kind – it was kinder for everyone if she lived, wasn’t it? All life, even a life as unimportant as hers, performed some kindness to those it touched; wouldn’t her husband, if no one else, appreciate this kindness? Or perhaps that was just vanity – she hadn’t destroyed the note, but had smoothed it into their diary on the kitchen table, as one might a shopping list, or a love letter, or a poem; but Patrick had never noticed it, because he didn’t make appointments, she supposed. She eventually screwed it up and put it into the recycling box, which Patrick did take care of, judiciously separating paper, glass and plastic. He still didn’t see it – or if he did, he saw it as just another piece of paper. Patrick, ironically for a medical professional whose job is to observe, seems to see very little indeed, at least when it comes to her. He persistently mistakes her for someone better than she is, as though his gaze stops just short of her. He frequently expresses his love for her, but the truth is that he doesn’t know her very well, and she is sure that should he need to fill out a missing persons form, he would be distressed to realize that he doesn’t know her height, her weight, her dress size. He would possibly even be unsure of her exact age and birthday. Although he would probably get her hair and eyes right, as she has the same hair and eyes as almost every woman of Bengali descent. She imagines him filling out this part of the form with confidence, with relief, even; hair: black, eyes: brown.

She supposes that such a note should say the truth about why she is leaving, but there is no larger truth. There is nothing significant. There is no Big Important Question to be answered. She has not had an affair, she is not in trouble with the law or in debt, she does not hate him or dislike him at all: like most couples, they fight and bicker all the time, about the ridiculous minutiae of their shared life; who last loaded the dishwasher, and where the toilet roll should be stored. They argue about her refusal, thus far, to consider pregnancy and whether to spend Christmas with the in-laws. There is really nothing but the trivial problems of the everyday, and to other people she looks like nothing so much as an ordinary woman, recently married, as yet childless, with ordinary cares. She looks like this even to herself, on occasion; an ordinary woman, in an ordinary life, wondering why she has striven to be ordinary above everything else. Perhaps she expected it would bring her peace of mind, bringing together the pieces of mind that still inhabit her, their little voices whining inside like shards of glass waiting to pierce through her skin and reveal how sliced up and fragmented she has secretly been within herself, for such a long time. The only thing that currently makes her more than ordinary, extraordinary even, is that she has written and recycled a suicide note, without anyone in the world noticing, and that she has decided to stop fighting, and go home.

„Über diesen Titel“ kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Weitere beliebte Ausgaben desselben Titels

Suchergebnisse für Half Life

Half Life

Anbieter: World of Books (was SecondSale), Montgomery, IL, USA

Zustand: Good. Item in good condition. Textbooks may not include supplemental items i.e. CDs, access codes etc. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers 00089949940

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Half Life

Anbieter: Jenson Books Inc, Logan, UT, USA

hardcover. Zustand: Good. The item is in good condition and works perfectly, however it is showing some signs of previous ownership which could include: small tears, scuffing, notes, highlighting, gift inscriptions, and library markings. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers 4BQGBJ010QN4

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Half Life

Anbieter: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, USA

Zustand: Good. Former library copy. Pages intact with minimal writing/highlighting. The binding may be loose and creased. Dust jackets/supplements are not included. Includes library markings. Stock photo provided. Product includes identifying sticker. Better World Books: Buy Books. Do Good. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers 3184958-6

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 2 verfügbar

Half Life

Anbieter: Library House Internet Sales, Grand Rapids, OH, USA

Hardcover. Zustand: Good. Zustand des Schutzumschlags: Good. Former library book. Mylar protector included. Binding is very loose. Please note the image in this listing is a stock photo and may not match the covers of the actual item. Ex-Library. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers 123585571

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Half Life

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Atlanta, AUSTELL, GA, USA

Hardcover. Zustand: Very Good. No Jacket. May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers G0312577907I4N00

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Half Life

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Dallas, Dallas, TX, USA

Hardcover. Zustand: Very Good. No Jacket. May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers G0312577907I4N00

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Half Life Farooki, Roopa

Anbieter: Desoto Books, Tampa, FL, USA

Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers D0-SIWQ-HBHF

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Half Life

Anbieter: WeBuyBooks, Rossendale, LANCS, Vereinigtes Königreich

Zustand: Very Good. Most items will be dispatched the same or the next working day. A copy that has been read, but is in excellent condition. Pages are intact and not marred by notes or highlighting. The spine remains undamaged. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers wbs3314510527

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand von Vereinigtes Königreich nach USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Half Life (SCARCE FIRST AMERICAN EDITION, FIRST PRINTING SIGNED BY AUTHOR, ROOPA FAROOKI)

Anbieter: Greystone Books, Margate, Vereinigtes Königreich

Paperback. Zustand: Very Good. First American Edition, First Printing. VG. First American Edition, First Printing. Paperback. (xii),259pp. PRESENTATION COPY INSCRIBED AND SIGNED BY AUTHOR, ROOPA FAROOKI. Signing reads, 'For ----/All best wishes/Roopa/Farooki'. A novel in which Aruna Jones walks out of her London apartment to return to her life in Singapore. A SCARCE first American edition, first printing SIGNED BY AUTHOR, ROOPA FAROOKI. Presentation Copy Inscribed & Signed. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers 20414

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand von Vereinigtes Königreich nach USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar