Inhaltsangabe

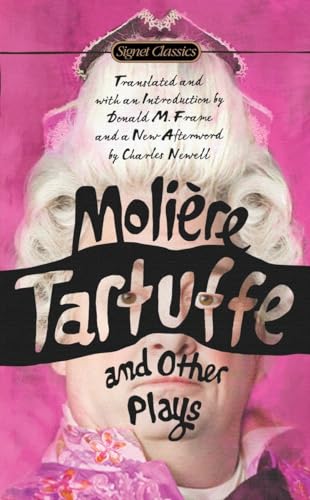

The Ridiculous Precieuses * The School for Husbands * The School for Wives * The Critique of the School for Wives * The Versailles Impromptu * Tartuffe * Don Juan

This memorable collection gathers the plays of the great social satirist and playwright Molière, representing the many facets of his genius and offering a superb introduction to the comic inventiveness, richness of prose, and insight that make up Molière’s enduring legacy to theater, literature, and the world.

Translated and with an Introduction by Donald M. Frame, a Foreword by Virginia Scott, and a New Afterword

Die Inhaltsangabe kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Über die Autorin bzw. den Autor

Molière, born Jean-Baptiste Poquelin in1622, began his career as an actor before becoming a playwright who specialized in satirizing the institutions and morals of his day. In 1658, his theater company settled in Paris in the Théâter du Petit-Bourbon. The object of fierce attack because of such masterpieces as Tartuffe and Don Juan, Molière nonetheless won the favor of the public. In 1665, his company became the King’s Troupe, and the following year saw the staging of The Misanthrope, as well as The Doctor in Spite of Himself. In 1668, he produced his bitterly comic The Miser and, in the remaining years before his death, created such plays as The Would-Be Gentleman, The Mischievous Machinations of Scapin, and The Learned Women. In 1673, Molière collapsed onstage while performing his last play, The Imaginary Invalid, and died shortly thereafter.

Donald M. Frame was Moore Professor of French at Columbia University and an acclaimed scholar and translator of French literature. Among his notable works of translation are The Complete Essays of Montaigne, The Complete Works of Rabelais, and the Signet Classics Tartuffe & Other Plays and Candide, Zadig, and Selected Stories.

Virginia Scott is Professor Emerita in the Department of Theater of the University of Massachusetts at Amherst. She is the author of Moliére: A Theatrical Life, The Commedia Dell’Arte in Paris, and Performance, Poetry and Politics on the Queen’s Day: Catherine de Medici and Pierre de Ronsard at Fontainebleau (with Sara Sturm-Maddox).

Auszug. © Genehmigter Nachdruck. Alle Rechte vorbehalten.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

TITLE PAGE

COPYRIGHT

INTRODUCTION

SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY

Introduction

Molière is probably the greatest and best-loved French author, and comic author, who ever lived. To the reader as well as the spectator, today as well as three centuries ago, the appeal of his plays is immediate and durable; they are both instantly accessible and inexhaustible. His rich resources make it hard to decide, much less to agree, on the secret of his greatness. After generations had seen him mainly as a moralist, many critics today have shifted the stress to the director and actor whose life was the comic stage; but all ages have rejoiced in three somewhat overlapping qualities of his: comic inventiveness, richness of fabric, and insight.

His inventiveness is extraordinary. An actor-manager-director-playwright all in one, he knew and loved the stage as few have done, and wrote with it and his playgoing public always in mind. In a medium in which sustained power is one of the rarest virtues, he drew on the widest imaginable range, from the broadest slapstick to the subtlest irony, to carry out the arduous and underrated task of keeping an audience amused for five whole acts. Working usually under great pressure of time, he took his materials where he found them, yet always made them his own.

The fabric of his plays is rich in many ways: in the intense life he infuses into his characters; in his constant preoccupation with the comic mask, which makes most of his protagonists themselves—consciously or unconsciously—play a part, and leads to rich comedy when their nature forces them to drop the mask; and in the weight of seriousness and even poignancy that he dares to include in his comic vision. Again and again he leads us from the enjoyable but shallow reaction of laughing at a fool to recognizing in that fool others whom we know, and ultimately ourselves; which is surely the truest and deepest comic catharsis.

Molière’s insight makes his characters understandable and gives a memorable inevitability to his comic effects. He is seldom completely realistic, of course; his characters, for example, tend to give themselves away more generously and laughably than is customary in life; but it is their true selves they give away. It is an obvious trick, and not very realistic, to have Orgon in Tartuffe (Act I, scene 4) reply four times to the account of his wife’s illness with the question “And Tartuffe?” and reply, again four times, to each report of Tartuffe’s gross health and appetite, “Poor fellow!” But it shows us, rapidly and comically, that Orgon’s obsession has closed his mind and his ears to anything but what he wants to see and hear. In the following scene, it may be unrealistic to have him in one speech (ll. 276–79) boast of learning from Tartuffe such detachment from worldly things that he could see his whole family die without concern, and in the very next speech (ll. 306–10) praise Tartuffe for the scrupulousness that led him to reproach himself for killing a flea in too much anger. But—again apart from the sheer comedy—it is a telling commentary on the distortion of values that can come from extreme points of view. One of Molière’s favorite authors, Montaigne, had written about victims of moral hubris: “They want to get out of themselves and escape from the man. That is madness: instead of changing into angels, they change into beasts.” Molière is presenting the same idea dramatically, as he does with even more power later (Act IV, scene 3, l. 1293), when Orgon’s daughter has implored him not to force her to marry the repulsive Tartuffe, and he summons his will to resist her with these words:

Be firm, my heart! No human weakness now!

These moments of truth, these flashes of unconscious self-revelation that plunge us into the very center of an obsession, abound in Molière, adding to our insight even as they reveal his. And even as he caricatures aspects of himself in the reforming Alceste or in the jealous older lover in Arnolphe, so he imparts to his moments of truth not only the individuality of the particular obsession but also the universality of our common share in it.

* * *

Molière is one of those widely known public figures whose private life remains veiled. In his own time gossip was rife, but much of it comes from his enemies and is suspect. Our chief other source is his plays; but while these hint at his major concerns and lines of meditation, we must beware of reading them like avowals or his roles like disguised autobiography.*

He was born Jean-Baptiste Poquelin in Paris early in 1622 and baptized on January 15, the first son of a well-to-do bourgeois dealer in tapestry and upholstery. In 1631 his father bought the position of valet de chambre tapissier ordinaire du roi, and six years later obtained the right to pass it on at his own death to his oldest son, who took the appropriate “oath of office” at the age of fifteen. Together with many sons of the best families, Jean-Baptiste received an excellent education from the Jesuit Fathers of the Collège de Clermont. He probably continued beyond the basic course in rhetoric to two years of philosophy and then law school, presumably at Orléans.

Suddenly, as it appears to us, just as he was reaching twenty-one, he resigned his survival rights to his father’s court position, and with them the whole future that lay ahead of him; drew his share in the estate of his dead mother and a part of his own prospective inheritance; and six months later joined in forming, with and around Madeleine Béjart, a dramatic company, the Illustre-Théâtre. In September 1643 they rented a court-tennis court to perform in; in October they played in Rouen; in January 1644 they opened in Paris; in June young Poquelin was named head of the troupe, and signed himself, for the first time we know of, “de Molière.”

Molière’s was an extraordinary decision. Apart from the financial hazards, his new profession stood little above pimping or stealing in the public eye and automatically involved minor excommunication from the Church. To write for the theater, especially tragedy, carried no great onus; to be an actor, especially in comedy and farce, was a proof of immorality. Though Richelieu’s passion for the stage had improved its prestige somewhat, this meant only that a few voices were raised to maintain its possible innocence against the condemnation of the vast majority.

Obviously young Molière was in love with the theater, and had to act. He may also have been already in love with Madeleine Béjart; their contemporaries were probably right in thinking them lovers, though all we actually know is that they were stanch colleagues and business partners. Their loyalty was tested from the first. Although the Béjarts raised all the money they could, after a year and a half in Paris the company failed and had to break up; Molière was twice imprisoned in the Châtelet for debt; he and the Béjarts left Paris to try their luck in the provinces. For twelve years they were on the road, mainly in the south.

For the first five of these they joined the company, headed by Du Fresne, of the Duc d’Épernon in Guyenne. When d’Épernon dropped them, Molière became head of the troupe. From 1653 to 1657 they were in the service of a great prince of the blood, the Prince de Conti, until his conversion. Even with a noble patron, the life was nomadic and precarious, and engagements hard to get. However, the company gradually made a name for itself and prospered. Molière gained a rich...

„Über diesen Titel“ kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Weitere beliebte Ausgaben desselben Titels

Suchergebnisse für Tartuffe and Other Plays (Signet Classics)

Tartuffe and Other Plays (Signet Classics)

Anbieter: Orion Tech, Kingwood, TX, USA

Mass Market Paperback. Zustand: Fair. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers 0451474317-4-34897740

Tartuffe and Other Plays (Signet Classics)

Anbieter: World of Books (was SecondSale), Montgomery, IL, USA

Zustand: Very Good. Item in very good condition! Textbooks may not include supplemental items i.e. CDs, access codes etc. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers 00095106765

Tartuffe and Other Plays (Signet Classics)

Anbieter: World of Books (was SecondSale), Montgomery, IL, USA

Zustand: Good. Item in good condition. Textbooks may not include supplemental items i.e. CDs, access codes etc. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers 00091820657

Tartuffe and Other Plays (Signet Classics)

Anbieter: World of Books (was SecondSale), Montgomery, IL, USA

Zustand: Acceptable. Item in acceptable condition! Textbooks may not include supplemental items i.e. CDs, access codes etc. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers 00084213777

Tartuffe and Other Plays (Signet Classics)

Anbieter: Greenworld Books, Arlington, TX, USA

Zustand: acceptable. Fast Free Shipping â" A well-loved copy with text fully readable and cover pages intact. May display wear such as writing, highlighting, bends, folds or library marks. Still a complete and usable book. Supplemental items like CDs or access codes may not be included. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers GWV.0451474317.A

TARTUFFE AND OTHER PLAYS (SIGNET

Anbieter: Goodwill of Colorado, COLORADO SPRINGS, CO, USA

Zustand: acceptable. This item is in overall acceptable condition. Covers and dust jackets are intact but may have heavy wear including creases, bends, edge wear, curled corners or minor tears as well as stickers or sticker-residue. Pages are intact but may have minor curls, bends or moderate to considerable highlighting writing. Binding is intact; however, spine may have heavy wear. Digital codes may not be included and have not been tested to be redeemable and or active. A well-read copy overall. Please note that all items are donated goods and are in used condition. Orders shipped Monday through Friday! Your purchase helps put people to work and learn life skills to reach their full potential. Orders shipped Monday through Friday. Your purchase helps put people to work and learn life skills to reach their full potential. Thank you! Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers 466OE3003W4M

Tartuffe and Other Plays (Signet Classics)

Anbieter: Goodwill of Colorado, COLORADO SPRINGS, CO, USA

Zustand: good. All pages and cover are intact. Dust jacket included if applicable, though it may be missing on hardcover editions. Spine and cover may show minor signs of wear including scuff marks, curls or bends to corners as well as cosmetic blemishes including stickers. Pages may contain limited notes or highlighting. "From the library of" labels may be present. Shrink wrap, dust covers, or boxed set packaging may be missing. Bundled media e.g., CDs, DVDs, access codes may not be included. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers 466QI00012B5

Tartuffe and Other Plays (Signet Classics)

Anbieter: HPB Inc., Dallas, TX, USA

Mass Market Paperback. Zustand: Very Good. Connecting readers with great books since 1972! Used books may not include companion materials, and may have some shelf wear or limited writing. We ship orders daily and Customer Service is our top priority! Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers S_439366967

Tartuffe and Other Plays

Anbieter: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, USA

Zustand: Very Good. Former library book; may include library markings. Used book that is in excellent condition. May show signs of wear or have minor defects. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers 6167875-6

Tartuffe and Other Plays

Anbieter: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, USA

Zustand: Good. Former library book; may include library markings. Used book that is in clean, average condition without any missing pages. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers 6167874-6