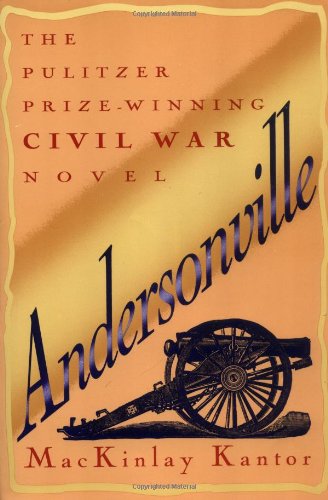

Inhaltsangabe

In 1864, thirty-three thousand Yankee prisoners of war suffer the horrors of imprisonment at the Confederate prison of Andersonville

Die Inhaltsangabe kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Über die Autorin bzw. den Autor

MACKINLAY KANTOR (1904-1977) was the distinguished author of more than thirty books and numerous screenplays.

Auszug. © Genehmigter Nachdruck. Alle Rechte vorbehalten.

I

Sometimes there was a compulsion which drew Ira Claffey from his plantation and sent him to walk the forest. It came upon him at eight o’clock on this morning of October twenty-third; he responded, he yielded, he climbed over the snake fence at the boundary of his sweet potato field and went away among the pines.

Ira Claffey had employed no overseer since the first year of the war, and had risen early this morning to direct his hands in the potato patch. Nowadays there were only seven and one-half hands on the place, house and field, out of a total Negro population of twelve souls; the other four were an infant at the breast and three capering children of shirt-tail size.

Jem and Coffee he ordered to the digging, and made certain that they were thorough in turning up the harvest and yet gentle in lifting the potatoes. Nothing annoyed Ira Claffey like storing a good thirty-five bushels in a single mound and then losing half of them through speedy decay.

In such a manner, he thought, have some of our best elements and institutions perished. One bruise, one carelessness, and rot begins. Decay is a secret but hastening act in darkness; then one opens up the pine bark and pine straw—or shall we say, the Senate?—and observes a visible wastage and smell, a wet and horrid mouldering of the potatoes. Or shall we say, of the men?

In pursuit of his own husbandry on this day, Ira carried a budding knife in his belt. While musing in bed the night before, he had been touched with ambition: he would bud a George the Fourth peach upon a Duane’s Purple plum.

Veronica was not yet asleep, but reading her Bible by candlelight beside him. He told her about it.

But, Ira, does not the Duane’s Purple ripen too soon? Aren’t those the trees just on the other side of the magnolias?

No, no, my dear. Those are Prince’s Yellow Gage. The Duane’s Purple matures in keeping with the George Fourths. I’d warrant you about the second week of July. Say about the tenth. I should love to see that skin. Such a fine red cheek on the George Fourths, and maybe dotted with that lilac bloom and yellow specks—

But she was not hearing him, she was weeping. He turned to watch her; he sighed, he put out one big hand and touched the thick gray-yellow braid which weighted on her white-frilled shoulder. It was either Moses or Sutherland whom she considered now. Dully he wondered which one.

She said, on receiving the communication of his thought, though he had said nothing— She spoke Suthy’s name.

Oh, said Ira. I said nothing to make you think—

The Prince’s Yellow Gage. He fancied them so. When they were still green he’d hide them in the little waist he wore. Many’s the time I gave him a belting—

She sobbed a while longer, and he stared into the gloom beyond the bed curtains, and did his best to forget Suthy. Suthy was the eldest. Sixteenth Georgia. It was away up at the North, at a place no one had ever heard of before, a place called Gettysburg.

In recent awareness of bereavement had lain the germ of retreat and restlessness, perhaps; but sometimes Ira spirited himself off into the woods when he was fleeing from no sadness or perplexity. He had gone like that since he could first remember. Oh, pines were taller forty-five years ago . . . when he was only three feet tall, the easy nodding grace of their foliage was reared out of all proportion, thirty times his stature. And forests were wilder, forty-five years ago, over in Liberty County, and he went armed with a wooden gun which old Jehu had carved and painted as a Christmas gift for him. It had a real lock, a real flint; it snapped and the sparks flew. Ira Claffey slew brigades of redcoats with this weapon; he went as commander of a force of small blacks; he was their general.

Hi, them’s British, Mastah Iry.

Where?

Yonder in them ’simmons!

Take them on the flank.

Hi, what you say we do, Mastah?

He wasn’t quite sure what he wanted them to do. Something about the flank. His Uncle Sutherland talked about a flank attack in some wild distant spot known as the Carolinas. . . . Of course this was later on, perhaps only forty years ago, when Ira Claffey was ten. . . .

Charge those redcoats! They advanced upon the persimmon brake in full cry and leaping; and once there came terror when a doe soared out of the thicket directly in their faces, and all the little darkies scattered like quail, and Ira came near to legging it after them.

In similar shades he had been Francis Marion, and surely his own boys had scuttled here in identical pursuits. It was a good place to be, treading alone on the clay-paved path curving its way to the closest branch of Sweetwater Creek. God walked ahead and behind and with him, near, powerful, silent . . . words of my mouth, and the meditation of my heart, be acceptable in thy sight, O Lord, my strength, and my redeemer.

He had budded the peach upon the plum as he wished to do, though he feared that it was a trifle too late in the season for success. He budded each of the two selected trees five times, and then went back to the potato field. Coffee and Jem were doing well enough, but they were plaguèd slow; Ira had been emphatic about the tenderness he required of them, and they handled the big sulphur-colored Brimstones as if they were eggs. Well, he thought, I shan’t speed them on this. Better forty bushels well-dug and well-stored than eighty bushels bumped and scratched and ready to spoil as soon as they’re covered.

Keep on with it until I return, and mind about no bruising. I shall look up some pine straw—where it’s thickest and easy to scoop—and we’ll fetch the cart after the nooning.

Yassah.

Frost had not yet killed the vines. Some planters always waited for a killing frost before they dug, but Ira was certain that the crop kept better if dug immediately before the frost struck.

He was newly come into his fifty-first year; the natal day had been observed on October sixth. Black Naomi chuckled mysteriously in the kitchen; there had been much talk about, Mistess, can I please speak with you a minute alone? He had to pretend that he was blind and deaf, and owned no suspicion that delicate and hard-to-come-by substances were being lavished in his honor. The fragrant Lady Baltimore cake appeared in time, borne by Ira Claffey’s daughter because she would not trust the wenches with this treasure.

There they sat, the three surviving Claffeys left at home, sipping their roast-grain coffee and speaking words in praise of the cake, and now Ira had lived for half a century . . . fifty years stuffed with woe and work and dreams and peril. He sought to dwell in recollection only on the benefits accruing. With Veronica and Lucy he tried to keep his imaginings away from far-off roads where horses and men were in tragic operation.

The best I’ve tasted since the Mexican War.

Poppy, you always say that. About everything.

Come, come, Lucy. Do I indeed?

You do, agreed his wife, and gave him her wan smile above the home-dipped candles.

Yes, sir, chimed in Lucy. It’s always the best and the worst and the biggest and all such things, but always dated from that old war.

After this night, said Ira, I presume that I should date everything from my fiftieth birthday?

Poppy, love, you don’t look even on the outskirts of fifty. Scarcely a shred of gray in your hair.

Well, my dear, I don’t have much hair left to me.

That’s no certain indication of encroaching age. Is it, Mother? Take Colonel Tollis. I declare, he...

„Über diesen Titel“ kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Weitere beliebte Ausgaben desselben Titels

Suchergebnisse für Andersonville (Plume)

Andersonville

Anbieter: World of Books (was SecondSale), Montgomery, IL, USA

Zustand: Good. Item in good condition. Textbooks may not include supplemental items i.e. CDs, access codes etc. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers 00093126797

Andersonville

Anbieter: World of Books (was SecondSale), Montgomery, IL, USA

Zustand: Acceptable. Item in acceptable condition! Textbooks may not include supplemental items i.e. CDs, access codes etc. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers 00095265732

Andersonville

Anbieter: Evergreen Goodwill, Seattle, WA, USA

paperback. Zustand: Good. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers mon0000294932

Andersonville (Plume)

Anbieter: World of Books (was SecondSale), Montgomery, IL, USA

Zustand: Good. Item in good condition. Textbooks may not include supplemental items i.e. CDs, access codes etc. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers 00084287927

Andersonville

Anbieter: Wonder Book, Frederick, MD, USA

Zustand: Good. Good condition. A copy that has been read but remains intact. May contain markings such as bookplates, stamps, limited notes and highlighting, or a few light stains. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers X06E-01406

Andersonville (Plume)

Anbieter: HPB-Diamond, Dallas, TX, USA

Paperback. Zustand: Very Good. Connecting readers with great books since 1972! Used books may not include companion materials, and may have some shelf wear or limited writing. We ship orders daily and Customer Service is our top priority! Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers S_444658501

Andersonville (Plume)

Anbieter: Half Price Books Inc., Dallas, TX, USA

Paperback. Zustand: Very Good. Connecting readers with great books since 1972! Used books may not include companion materials, and may have some shelf wear or limited writing. We ship orders daily and Customer Service is our top priority! Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers S_427260410

Andersonville

Anbieter: Better World Books: West, Reno, NV, USA

Zustand: Good. Reprint. Used book that is in clean, average condition without any missing pages. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers GRP101973128

Andersonville

Anbieter: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, USA

Zustand: Good. Reprint. Used book that is in clean, average condition without any missing pages. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers GRP101973128

Andersonville (Plume)

Anbieter: HPB Inc., Dallas, TX, USA

Paperback. Zustand: Very Good. Connecting readers with great books since 1972! Used books may not include companion materials, and may have some shelf wear or limited writing. We ship orders daily and Customer Service is our top priority! Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers S_441369130