Verwandte Artikel zu Kierkegaard's Writings, II, Volume 2: The Concept...

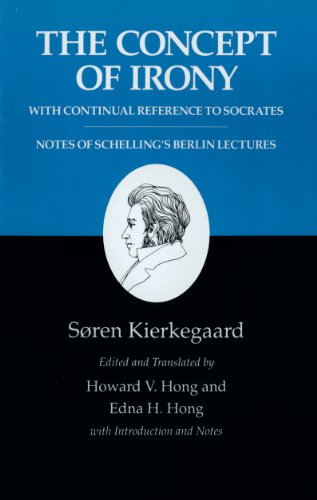

Kierkegaard's Writings, II, Volume 2: The Concept of Irony, with Continual Reference to Socrates/Notes of Schelling's Berlin Lectures (Kierkegaard's Writings, 2) - Softcover

Inhaltsangabe

A work that "not only treats of irony but is irony," wrote a contemporary reviewer of The Concept of Irony, with Continual Reference to Socrates. Presented here with Kierkegaard's notes of the celebrated Berlin lectures on "positive philosophy" by F.W.J. Schelling, the book is a seedbed of Kierkegaard's subsequent work, both stylistically and thematically. Part One concentrates on Socrates, the master ironist, as interpreted by Xenophon, Plato, and Aristophanes, with a word on Hegel and Hegelian categories. Part Two is a more synoptic discussion of the concept of irony in Kierkegaard's categories, with examples from other philosophers and with particular attention given to A. W. Schlegel's novel Lucinde as an epitome of romantic irony.

The Concept of Irony and the Notes of Schelling's Berlin Lectures belong to the momentous year 1841, which included not only the completion of Kierkegaard's university work and his sojourn in Berlin, but also the end of his engagement to Regine Olsen and the initial writing of Either/Or.

Die Inhaltsangabe kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Über die Autorin bzw. den Autor

Charlotte y Peter Fiell son dos autoridades en historia, teoría y crítica del diseño y han escrito más de sesenta libros sobre la materia, muchos de los cuales se han convertido en éxitos de ventas. También han impartido conferencias y cursos como profesores invitados, han comisariado exposiciones y asesorado a fabricantes, museos, salas de subastas y grandes coleccionistas privados de todo el mundo. Los Fiell han escrito numerosos libros para TASCHEN, entre los que se incluyen 1000 Chairs, Diseño del siglo XX, El diseño industrial de la A a la Z, Scandinavian Design y Diseño del siglo XXI.

Auszug. © Genehmigter Nachdruck. Alle Rechte vorbehalten.

The Concept of Irony with Continual Reference to Socrates

By Søren Kierkegaard, Howard V. Hong, Edna H. HongPRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

All rights reserved.

Contents

Historical Introduction,

The Concept of Irony, with Continual Reference to Socrates,

Theses,

Part One THE POSITION OF SOCRATES VIEWED AS IRONY,

Introduction,

I The View Made Possible,

II The Actualization of the View,

III The View Made Necessary,

Appendix Hegel's View of Socrates,

Part Two THE CONCEPT OF IRONY,

Introduction,

Observations for Orientation,

The World-Historical Validity of Irony, the Irony of Socrates,

Irony after Fichte,

Irony as a Controlled Element, the Truth of Irony,

Addendum NOTES OF SCHELLING'S BERLIN LECTURES,

Supplement,

Key to References,

Original Title Pages of The Concept of Irony,

Original First Page (manuscript) of Notes of Schelling's Berlin Lectures,

Selected Entries from Kierkegaard's Journals and Papers Pertaining to The Concept of Irony,

Editorial Appendix,

Acknowledgments,

Collation of The Concept of Irony in the Danish Editions of Kierkegaard's Collected Works,

Notes,

Bibliographical Note,

Index,

CHAPTER 1

The View Made Possible [XIII 109]

We shall now move to a summary of the views of Socrates provided by his closest contemporaries. In this respect there are three who command our attention: Xenophon, Plato, and Aristophanes. I cannot fully agree with Baur, who thinks that, along with Plato, Xenophon should be most highly regarded. Xenophon stopped with Socrates' immediacy and thus has definitely misunderstood him in many ways; whereas Plato and Aristophanes have blazed a trail through [XIII 110] the tough exterior to a view of the infinity that is incommensurable with the multifarious events of his life. Thus it can be said of Socrates that just as he walked through life continually between a caricature and the ideal, so after his death he continues to stroll between those two. As for the relation between Xenophon and Plato, Baur is correct in saying on page 123: "Zwischen diesen Beiden tritt uns aber sogleich eine Differenz entgegen, die in mancher Hinsicht mit dem bekannten Verhältnisz verglichen werden kann, welches zwischen den synoptischen Evangelien und dem des Johannes stattfindet. Wie die synoptischen Evangelien zunächst mehr nur die äussere, mit der jüdischen Messias-Idee zusammenhängende, Seite der Erscheinung Christi darstellen, das johanneische aber vor allem seine höhere Natur und das unmittelbar Göttliche in ihm ins Auge faszt, so hat auch der platonische Sokrates eine weit höhere ideellere Bedeutung als der xenophontische, mit welchem wir uns im Grunde immer nur auf dem Boden der Verhältnisse des unmittelbaren praktischen Lebens befinden [Yet we instantly encounter a difference between these two that in many respects may be likened to the well-known relation between the Synoptic Gospels and the Gospel of John. Just as the Synoptic Gospels present primarily only the external aspect of Christ's appearance, the aspect connected with the Jewish idea of the Messiah, whereas the Gospel of John above all captures his higher nature and the immediately divine within him, so also the Platonic Socrates does indeed have an ideal significance far higher than the Xenophontic Socrates, with whom we in effect always find ourselves on the flat and even level of conditions belonging to the immediate practical life]." Baur's comment is not only striking but also to the point when one remembers that Xenophon's view of Socrates differs from the Synoptic Gospels in that the latter merely recorded the immediate, accurate picture of Christ's immediate existence (which, please note, did not signify anything else than what it was), and insofar as Matthew's seeming to have an apologetic objective, the [XIII 111] question at that time was to reconcile Christ's life with the idea of the Messiah, whereas Xenophon is dealing with a man whose immediate existence means something else than meets the eye at first glance, and insofar as he mounts a defense of him, he does this only in the form of an appeal to a subtilizing, right-honorable age. On the other hand, the comment about Plato's relation to John is also correct if one simply holds fast to the position that John found and immediately perceived in Christ everything that he, precisely by restraining himself to silence, presents in all its objectivity, because his eyes were opened to the immediate divinity in Christ; whereas Plato creates his Socrates by means of poetic productivity, since Socrates, precisely in his immediate existence, was only negative.

But first an exposition of each one separately.

XENOPHON

As a preliminary, we must recall that Xenophon had an objective (this is already a deficiency or an irksome redundancy) — namely, to show what a scandalous injustice it was for the Athenians to condemn Socrates to death. Indeed, Xenophon succeeded in this to such a singular degree that one would be more inclined to believe that it was Xenophon's objective to prove that it was foolishness or an error on the part of the Athenians to condemn Socrates, for Xenophon defends Socrates in such a way that he renders him not only innocent but also altogether innocuous — so much so that we wonder greatly about what kind of daimon must have bewitched the Athenians to such a degree that [XIII 112] they were able to see more in him than in any other good-natured, garrulous, droll character who does neither good nor evil, does not stand in anyone's way, and is so fervently well-intentioned toward the whole world if only it will listen to his slipshod nonsense. And what harmonia praestahilita [preestablished harmony] in lunacy, what higher unity in madness is there not inherent in Plato's and the Athenians' uniting to put to death and immortalize such a good-natured bourgeois as that? This, after all, would be an incomparable irony upon the world. Plato and the Athenians must have felt almost as uncomfortable with Xenophon's irenic intervention as one feels at times in an argument when — just as the point in dispute, precisely by being brought to a head, begins to be interesting — a helpful third party kindly takes it upon himself to reconcile the disputants, to take the whole matter back to a triviality. Finally, by eliminating all that was dangerous in Socrates, Xenophon actually reduced him totally in absurdum, in recompense, probably, for Socrates' having done this so often to others.

What makes it even more difficult to get a clear notion of Socrates' personality from Xenophon's account is the total lack of situation. The base on which the specific conversation moves is just as invisible and shallow as a straight line, just as monotonous as the single-color background that children and Nürnberg painters customarily use in their pictures. Yet situation was immensely important to Socrates' personality, which must have given an intimation of itself precisely by a secretive presence in and a mystical floating over the multicolored variety of exuberant Athenian life and which must have been explained by a duplexity of existence, much as the flying fish in relation to fish and birds. This emphasis on situation was especially significant in order to indicate that the true center for Socrates was not a fixed point but an ubique et nusquam [everywhere and nowhere], in order to accentuate the Socratic sensibility, which upon the most subtle and fragile contact immediately detected the presence of idea, promptly felt the corresponding electricity present in everything, in order to make graphic the genuine Socratic method, which found no phenomenon too humble a point of departure from which to work oneself up into the sphere of thought. This Socratic possibility of beginning anywhere, actualized in life (although it no doubt would most often be overlooked by the crowd, for whom the way they ever came upon this or that subject always remains a riddle, because their discussions often end and [XIII 113] begin in a stagnating village pond), this unerring Socratic magnifying glass for which no subject was so compact that he did not immediately discern the idea in it (not gropingly but with immediate sureness, and yet also with a practiced eye of his own for the apparent foreshortenings of perspective, and thus he did not attract the subject to him by subreption but simply kept the same ultimate prospect in sight, while for the listener and observer it emerged step by step), this Socratic modest frugality that formed such a sharp contrast to the Sophist's empty noise and unsatiating gorging — all this one might wish that Xenophon had let us perceive. And what life would then have come into the [XIII 114] presentation if in the midst of the bustling work of the artisans and the braying of the pack-asses one had discerned the divine woof with which Socrates interlaced the web of existence. If through the boisterous noise of the marketplace one had heard the divine fundamental harmony that resounded through existence [Tilværelse] (since for Socrates every single thing was a metaphorical and not inappropriate symbol of the idea), what an interesting conflict there would have been between the earthly life's most routine forms of expression and Socrates, who seemed to be saying the very same thing. This importance of situation is not lacking in Plato, however, although it is purely poetical, and thus demonstrates precisely its own validity and the lack in Xenophon.

But just as Xenophon on the one hand lacks an eye for situation, so on the other he lacks an ear for rejoinder. Not that the questions Socrates asks and the answers he gives are incorrect — on the contrary, they are all too correct, all too stubborn, all too tedious. With Socrates, rejoinder was not an immediate unity with what had been said, was not a flowing out but a continual flowing back, and what one misses in Xenophon is an ear for the infinitely resonating reverse echoing of the rejoinder in the personality (for as a rule the rejoinder is straightforward transmission of thought by way of sound). The more Socrates tunneled under existence [Existents], the more deeply and inevitably each single remark had to gravitate toward an ironic totality, a spiritual condition that was infinitely bottomless, invisible, and indivisible. Xenophon had no intimation whatever of this secret. Allow me to illustrate what I mean by a picture. There is a work that represents Napoleon's grave. Two tall trees shade the grave. There is nothing else to see in the work, and the unsophisticated observer sees nothing else. Between the two trees there is an empty space; as the eye follows the outline, suddenly Napoleon himself emerges from this nothing, and now it is impossible to have him disappear again. Once the eye has seen him, it goes on seeing him with an almost alarming necessity. So also with Socrates' rejoinders. One hears his words in the [XIII 115] same way one sees the trees; his words mean what they say, just as the trees are trees. There is not one single syllable that gives a hint of any other interpretation, just as there is not one single line that suggests Napoleon, and yet this empty space, this nothing, is what hides that which is most important. Just as in nature we find sites so remarkably arranged that those who stand closest to the one who is speaking cannot hear him and only those standing at a specific spot, often at some distance, can hear, so also with Socrates' rejoinders, if we only bear in mind that at this point to hear is identical with understanding and not to hear with misunderstanding. It is these two fundamental defects I must in a provisional way point out in Xenophon, and yet situation and rejoinder are the combination that makes up the personality's ganglionic and cerebral system.

We proceed now to a collection of observations found in Xenophon and attributed to Socrates. Generally speaking, these observations are so scrubby and stunted that it is not difficult but is deadening for the eye to take in the whole lot at one glance. Only rarely does an observation rise to a poetic or a philosophic thought; and despite the beautiful language, the exposition has exactly the same flavor as the profundities of our Folkeblad or the heavenly parish-clerk caterwauling of a nature-worshiping normal-school student.

[XIII 116] Proceeding now to the Socratic observations preserved by Xenophon, we shall attempt to trace their possible family resemblance, even though they often seem to be children of different marriages.

We trust that the readers will agree with our statement that [XIII 117] the empirical determinant is the polygon, that the intuition is the circle, and that the qualitative difference between them will continue forevermore. In Xenophon, gadding observation always wanders about in the polygon, presumably often victim of its own deception, when, just by having a good distance yet to go, it believes that it has found the true infinity and, like an insect crawling along a polygon, falls off because what appeared to be an infinity was only an angle.

In Xenophon, one of the points of departure for Socratic teaching is the useful. But the useful is simply the polygon, which corresponds to the interior infinity of the good emanating from and returning to itself, indifferent to none of its own elements but moving in all of them and totally in all of them and totally in each one. The useful has an infinite dialectic and also an infinite spurious dialectic. In other words, the useful is the external dialectic of the good, its negation, which detached becomes in itself merely a kingdom of shadows where nothing endures but everything formless and shapeless liquifies and volatilizes, all according to the observer's capricious and superficial glance, in which each individual existence is only an infinitely divisible fractional existence in a perpetual calculation. (The useful mediates everything for its own ends, even the useless, since, just as nothing is absolutely useful, [XIII 118] neither can anything be absolutely useless, because the absolutely useful is merely a fleeting element in the fitful changes of life.) This universal view of the useful is developed in the dialogue with Aristippus (Mem., III, 8). Whereas in Plato it is Socrates in particular who always takes his subject from the accidental concretion in which his associates see it and leads it on to the abstract, in Xenophon it is Socrates in particular who demolishes Aristippus's admittedly weak attempt to approach the idea. It is unnecessary to elaborate further on this dialogue, since Socrates' opening attitude simultaneously makes manifest the skilled fencer and the rules for the entire investigation. To Aristippus's question whether he knew anything good, he answers (para. 3): [TEXT NOT REPRODUCIBLE IN ASCII] [Are you asking if I know of anything good for a fever?]," whereby the discursive raisonnement [reasoning, line of argument] is immediately suggested. The whole dialogue then proceeds along this path with an imperturbability that does not circumvent the apparent paradox (para. 6): [TEXT NOT REPRODUCIBLE IN ASCII] [Is a dung-basket beautiful then? Of course, and a golden shield is ugly, if the one is well made for its special work and the other badly]." Although I have quoted this dialogue only as an example and thus must essentially take my stand on the total impact that is the vital force in the example, I shall nevertheless, having also cited it as an example instar omnium [worth them all, i.e., typical], call to mind the difficulty with respect to the manner in which Xenophon introduces this dialogue. He implies, namely, that it was a captious question on Aristippus's part, in order to embarrass Socrates with the infinite dialectic implicit in the good when understood as the useful. He suggests that Socrates saw through this trick. Thus it is conceivable that Xenophon preserved this whole dialogue as an example of Socrates' gymnastics. It might seem that possibly there was still a dormant irony in Socrates' whole deportment, that by seeming to enter unsuspectingly into the trap Aristippus had set for him he thereby demolished his cunning plot and made Aristippus the one who against his will had to advance the argument he had calculated that Socrates would have stressed. But anyone who knows Xenophon will surely find this highly improbable, and for additional ease of mind Xenophon has also provided a completely different reason why Socrates behaved in this manner — namely, "in order to benefit those around him." From this it is obvious, according to Xenophon's view, that [XIII 119] Socrates is in dead earnest when he takes the inspiring infinity of the inquiry back down to the underlying spurious infinity of the empirical.

The commensurable in general is Socrates' proper arena, and for the most part his activity consists of encircling all of man's thinking and doing with an insurmountable wall that shuts out all traffic with the world of ideas. Study of the sciences must not transgress this cordon of health either (Mem., IV, 7). One should learn enough geometry to help to see to it that one's fields are correctly measured; the further study of astronomy is deprecated and he advises against the speculations of Anaxagoras — in short, every science is reduced zum Gebrauch für Jedermann [for use by everyone].

(Continues...)

Excerpted from The Concept of Irony with Continual Reference to Socrates by Søren Kierkegaard, Howard V. Hong, Edna H. Hong. Copyright © 1989 Howard V. Hong. Excerpted by permission of PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS.

All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Excerpts are provided by Dial-A-Book Inc. solely for the personal use of visitors to this web site.

„Über diesen Titel“ kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Gebraucht kaufen

Zustand: BefriedigendEUR 6,82 für den Versand von USA nach Deutschland

Versandziele, Kosten & DauerNeu kaufen

Diesen Artikel anzeigenEUR 0,80 für den Versand von USA nach Deutschland

Versandziele, Kosten & DauerSuchergebnisse für Kierkegaard's Writings, II, Volume 2: The Concept...

The Concept of Irony/Schelling Lecture Notes : Kierkegaard's Writings, Vol. 2 (Kierkegaard's Writings, 2)

Anbieter: BooksRun, Philadelphia, PA, USA

Paperback. Zustand: Good. Reprint. It's a preowned item in good condition and includes all the pages. It may have some general signs of wear and tear, such as markings, highlighting, slight damage to the cover, minimal wear to the binding, etc., but they will not affect the overall reading experience. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers 0691020728-11-1

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

The Concept of Irony, with Continual Reference to Socrates/Notes of Schelling's Berlin Lectures

Anbieter: Better World Books Ltd, Dunfermline, Vereinigtes Königreich

Zustand: Good. Reprint. Ships from the UK. Used book that is in clean, average condition without any missing pages. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers 5445501-6

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Kierkegaard`s Writings, II, Volume 2 â" The Concept of Irony, with Continual Reference to Socrates/Notes of Schelling`s Berlin Lectures (Kierkegaard's Writings, 2)

Anbieter: WorldofBooks, Goring-By-Sea, WS, Vereinigtes Königreich

Paperback. Zustand: Very Good. The book has been read, but is in excellent condition. Pages are intact and not marred by notes or highlighting. The spine remains undamaged. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers GOR008028995

Anzahl: 2 verfügbar

Kierkegaard`s Writings, II, Volume 2 â" The Concept of Irony, with Continual Reference to Socrates/Notes of Schelling`s Berlin Lectures (Kierkegaard's Writings, 2)

Anbieter: WeBuyBooks, Rossendale, LANCS, Vereinigtes Königreich

Zustand: Good. Most items will be dispatched the same or the next working day. A copy that has been read but remains in clean condition. All of the pages are intact and the cover is intact and the spine may show signs of wear. The book may have minor markings which are not specifically mentioned. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers wbs7529312537

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

The Concept of Irony/Schelling Lecture Notes : Kierkegaard's Writings, Vol. 2 (Kierkegaard's Writings, 2)

Anbieter: Snowden's Books, Santa Fe, NM, USA

Soft cover. Zustand: Good. Original paperback, 634 pages, index, some light, general wear with curling at cover corners; some fading to the covers, along spine; crease mark to back upper 1/4 cover. I did not find any marks within book, but there may be some very limited ones. Excellent resource. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers ABE-1756093481946

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

The Concept of Irony, with Continual Reference to Socrates/Notes of Schelling's Berlin Lectures

Anbieter: PBShop.store US, Wood Dale, IL, USA

PAP. Zustand: New. New Book. Shipped from UK. Established seller since 2000. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers WP-9780691020723

Anzahl: 15 verfügbar

Kierkegaard?s Writings, II, Volume 2: The Concept of Irony, with Continual Reference to Socrates/Notes of Schelling?s Berlin Lectures

Anbieter: Kennys Bookshop and Art Galleries Ltd., Galway, GY, Irland

Zustand: New. Presented with Kierkegaard's notes of the celebrated Berlin lectures on "positive philosophy" by FWJ Schelling, this book is a seedbed of Kierkegaard's subsequent work, both stylistically and thematically. It concentrates on Socrates, as interpreted by Xenophon, Plato, and Aristophanes, with a word on Hegel and Hegelian categories. Editor(s): Hong, Howard V.; Hong, Edna H. Series: Kierkegaard's Writings. Num Pages: 664 pages, black & white illustrations. BIC Classification: HPC. Category: (P) Professional & Vocational; (U) Tertiary Education (US: College). Dimension: 215 x 140 x 41. Weight in Grams: 772. . 1992. Paperback. . . . . Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers V9780691020723

Anzahl: 11 verfügbar

The Concept of Irony/Schelling Lecture Notes : Kierkegaard's Writings, Vol. 2 (Kierkegaard's Writings, 76)

Anbieter: Reclaimed Bookstore, Richmond, VA, USA

Trade Paperback. Zustand: Used. Forth Printing with minor bumps/wear at edges/corners. Pages are clean and bright. Spine is straight and tight. Overall a very good edition! Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers 64632

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

The Concept of Irony, with Continual Reference to Socrates/Notes of Schelling's Berlin Lectures

Anbieter: Rarewaves USA, OSWEGO, IL, USA

Paperback. Zustand: New. A work that "not only treats of irony but is irony," wrote a contemporary reviewer of The Concept of Irony, with Continual Reference to Socrates. Presented here with Kierkegaard's notes of the celebrated Berlin lectures on "positive philosophy" by F.W.J. Schelling, the book is a seedbed of Kierkegaard's subsequent work, both stylistically and thematically. Part One concentrates on Socrates, the master ironist, as interpreted by Xenophon, Plato, and Aristophanes, with a word on Hegel and Hegelian categories. Part Two is a more synoptic discussion of the concept of irony in Kierkegaard's categories, with examples from other philosophers and with particular attention given to A. W. Schlegel's novel Lucinde as an epitome of romantic irony. The Concept of Irony and the Notes of Schelling's Berlin Lectures belong to the momentous year 1841, which included not only the completion of Kierkegaard's university work and his sojourn in Berlin, but also the end of his engagement to Regine Olsen and the initial writing of Either/Or. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers LU-9780691020723

Anzahl: Mehr als 20 verfügbar

The Concept of Irony, with Continual Reference to Socrates/Notes of Schelling's Berlin Lectures

Anbieter: PBShop.store UK, Fairford, GLOS, Vereinigtes Königreich

PAP. Zustand: New. New Book. Shipped from UK. Established seller since 2000. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers WP-9780691020723

Anzahl: 11 verfügbar