Inhaltsangabe

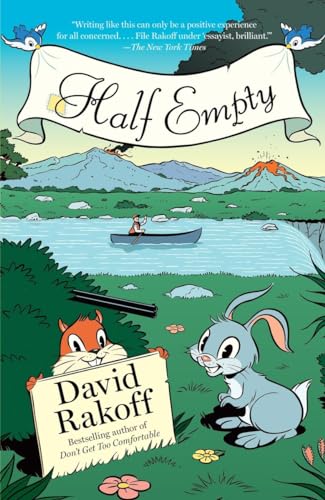

In this deeply smart and sneakily poignant collection of essays, the bestselling author of Fraud and Don’t Get Too Comfortable makes an inspired case for always assuming the worst—because then you’ll never be disappointed.

Whether he’s taking on pop culture phenomena with Oscar Wilde-worthy wit or dealing with personal tragedy, Rakoff’s sharp observations and humorist’s flair for the absurd will have you positively reveling in the untapped power of negativity.

Die Inhaltsangabe kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Über die Autorin bzw. den Autor

David Rakoff is the author of four New York Times bestsellers: the essay collections Fraud, Don’t Get Too Comfortable, and Half Empty, and the novel in verse Love, Dishonor, Marry, Die, Cherish, Perish. A two-time recipient of the Lambda Literary Award and winner of the Thurber Prize for American Humor, he was a regular contributor to Public Radio International’s This American Life. His writing frequently appeared in The New York Times, Newsweek, Wired, Salon, GQ, Outside, Gourmet, Vogue, and Slate, among other publications. An accomplished stage and screen actor, playwright, and screenwriter, he adapted the screenplay for and starred in Joachim Back’s film The New Tenants, which won the 2010 Academy Award for Best Live Action Short. He died in 2012.

Auszug. © Genehmigter Nachdruck. Alle Rechte vorbehalten.

The Bleak Shall Inherit

We were so happy. It was miserable.

Although it was briefly marvelous and strange to see a car parked outside an office, the wide hallway used like a street, many stories above the city.

The millennium had turned. The planes had not fallen from the sky, the trains had not careened off the tracks. Neither had the heart monitors, prenatal incubators, nor the iron lungs reset themselves to some suicidal zero hour to self-destruct in a lethal kablooey of Y2K shrapnel, as feared. And most important, the ATMs continued to dispense money, and what money it was.

I was off to see some of it. Like Edith Wharton's Gilded Age Buccaneers, when titled but cash-poor Europeans joined in wedlock with wealthy American girls in the market for pedigree, there were mutually abusive marriages popping up all over the city between un-moneyed creatives with ethereal Web-based schemes and the financiers who, desperate to get in on the action, bankrolled them. The Internet at that point was still newish and completely uncharted territory, to me, at least. I had walked away from a job at what would undoubtedly have been the wildly lucrative ground floor (1986, Tokyo) because it had seemed so boring, given my aggressive lack of interest in technology or machines, unless they make food. Almost fifteen years later, I was no more curious nor convinced, but now found myself at numerous parties for start-ups, my comprehension of which extended no further than the free snacks and drinks, and the perfume of money-scented elation in the air. The workings of "new media" remained entirely murky, and I a baffled hypocrite, scarfing down another beggar's purse with creme fraiche (flecked with just enough beads of caviar to get credit), pausing in my chewing only long enough to mutter "It'll never last." It was becoming increasingly difficult to fancy myself the guilelessly astute child at the procession who points out the emperor's nakedness as acquaintances were suddenly becoming millionaires on paper and legions of twenty-one-year-olds were securing lucrative and rewarding positions as "content providers" instead of answering phones for a living, as I had at that age. Brilliant success was all around.

So, so happy.

The surly Russian janitor (seemingly the only other New Yorker in a bad mood) rode me up in his dusty elevator in the vast deco building in the West Twenties, which was now home to cyber and design concerns that gravitated to its raw spaces and industrial cachet. The kind of place where the freight car and the corridors are both wide enough that you'd never have to get out of your Lexus until you'd parked it on the fourteenth floor.

Book publishing is always portrayed as teddibly genteel and literary: hunter-green walls, morocco-bound volumes, and some old codger in a waistcoat going on about dear Max Perkins. Worlds away from the reality of dropped-ceiling offices with seas of cubicles and mail-cart-scarred walls. But the Internet companies were coevolving with the fictionalized idealization of themselves. The way they looked in the movies was also how they looked in real life, much like real-life mobsters who now behave like the characters in the Godfather films.

The large industrial casement windows were masculine with grime, looking out over the rail yards on the open sky of West Side Manhattan. The content providers sat side by side at long metal trestle tables--the kind they use in morgues--providing content, the transparent turquoise bubbles of their iMacs shining like insect eyes. It was a painfully hip dystopia, some Orwellian Ministry of Malign Intent whose sheer stylishness made it a pleasure to be a chic and soulless drone; one's personal freedoms happily abrogated for a Hugo Boss jumpsuit.

I was there to interview the founders of a site that was to be the one stop where members of the media might log on to read about themselves and the latest magazine-world gossip, schadenfreude-laden items about hefty book advances and who was seen lunching at Michael's, etc. I will stipulate to a certain degree of prejudicial thinking before I even walked in. I expected a bunch of aphoristic, McLuhan-lite bushwa, something to justify the house-of-cards business model. But as a reporter, I was their target audience as well as a colleague. I was unprepared to be spoken to like an investor, as if I, too, were some venture capitalist who goes goggled-eyed and compliant at the mere mention of anything nonnumerical. I was being lubed up with snake oil, listening to a bunch of pronouncements that sounded definitive and guru-like on the surface but which upon examination seemed just plain old wrong.

"What makes a story really good and Webby," said one, "is, say, we post an item on David Geffen on a Monday, and then one of Geffen's people calls us to correct it, we can have a whole new version up by Tuesday." This was typical Dawn of the New Millennium denigration of print, which always seemed to lead to the faulty logic that it was not just the delivery system that was outmoded but such underlying practices as authoritative voice and credibility, fact-checking, editing, and impartiality that needed throwing out, too. It was a stance they both seemed a little old for, frankly, like watching a couple of forty-five-year-olds in backward baseball caps on skateboards. In the future, it seems, we would all take our editorial marching orders from the powerful subjects of our stories and it would be good (Right you are, Mr. Geffen!). It was a challenge to sit there and be told that caring about such things as journalistic independence or the desire to keep money's influence at even a show of remove meant one was clinging to old beliefs, a fossil in the making. Now that everything and everyone was palliated by the never-ending flow of revenue, there was no need to get exercised about such things, or about anything, really.

"We basically take John Seabrook's view that what you have is more important than what you believe. Whether you drive a Cadillac says more about you than if you're a Democrat or a Republican," said one, invoking a (print) journalist from The New Yorker.

Added the other: "That you watched The Sopranos last night is more important than who you voted for."

They weren't saying anything terribly incendiary. It's not like they were proposing tattooing people who have HIV the way odious William F. Buckley did (I'm sorry, I mean brilliant and courtly, such manners, and what a vocabulary! Nazi . . .). But we had just been through an electoral experience that had been bruising, to say the least. Who one voted for had almost never seemed more important, and they were saying it all so blithely. I felt like a wife who has caught her tobacco-and-gin-scented husband smeared in lipstick, a pair of silk panties sticking out of his jacket pocket, home after an unexplained three-day absence, listening to his giggling, sloppily improbable, and casually delivered alibi and being expected to swallow it while chuckling along.

We were silent for a moment, the only sound the keyboard tappings of the hipster minions. I finally managed to say, "I've just experienced the death of hope."

We all three laughed: me, in despair; them, all the way to the bank. Said one of them, "No, David. We are the very opposite. This is the birth of hope!"

Down in the rattling freight elevator. I couldn't face going home just then, where I would have to immediately relive this conversation by transcribing my tape. I turned right out of the building, crossed Eleventh Avenue, and sat on a concrete barrier facing the river. The cynicism of the interview, the lack of belief coupled with the enthusiastic tone in which the bullshit was being slung, the raiding-the-granaries greed dressed up in the cheap drag of some hollow dream of a Bright New Day of it all. The Hudson bleared and...

„Über diesen Titel“ kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Weitere beliebte Ausgaben desselben Titels

Suchergebnisse für Half Empty

Half Empty

Anbieter: ZBK Books, Carlstadt, NJ, USA

Zustand: good. Fast & Free Shipping â" Good condition with a solid cover and clean pages. Shows normal signs of use such as light wear or a few marks highlighting, but overall a well-maintained copy ready to enjoy. Supplemental items like CDs or access codes may not be included. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers ZWV.0767929055.G

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Half Empty

Anbieter: Gulf Coast Books, Cypress, TX, USA

paperback. Zustand: Good. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers 0767929055-3-31393163

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 2 verfügbar

Half Empty

Anbieter: Greenworld Books, Arlington, TX, USA

Zustand: good. Fast Free Shipping â" Good condition book with a firm cover and clean, readable pages. Shows normal use, including some light wear or limited notes highlighting, yet remains a dependable copy overall. Supplemental items like CDs or access codes may not be included. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers GWV.0767929055.G

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Half Empty

Anbieter: World of Books (was SecondSale), Montgomery, IL, USA

Zustand: Good. Item in good condition. Textbooks may not include supplemental items i.e. CDs, access codes etc. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers 00097328557

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Half Empty

Anbieter: Evergreen Goodwill, Seattle, WA, USA

paperback. Zustand: Good. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers mon0000361686

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Half Empty

Anbieter: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, USA

Zustand: Very Good. Used book that is in excellent condition. May show signs of wear or have minor defects. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers 5420146-6

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Half Empty

Anbieter: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, USA

Zustand: Good. Used book that is in clean, average condition without any missing pages. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers 4676017-6

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 3 verfügbar

Half Empty

Anbieter: Better World Books: West, Reno, NV, USA

Zustand: Good. Former library book; may include library markings. Used book that is in clean, average condition without any missing pages. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers 15049899-6

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Half Empty

Anbieter: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, USA

Zustand: Very Good. Former library book; may include library markings. Used book that is in excellent condition. May show signs of wear or have minor defects. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers GRP68616322

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Half Empty

Anbieter: HPB-Red, Dallas, TX, USA

paperback. Zustand: Very Good. Connecting readers with great books since 1972! Used textbooks may not include companion materials such as access codes, etc. May have some wear or limited writing/highlighting. We ship orders daily and Customer Service is our top priority! Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers S_438074425

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar