Inhaltsangabe

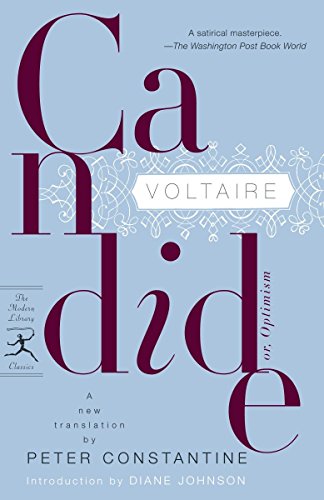

In this splendid new translation of Voltaire’s satiric masterpiece, all the celebrated wit, irony, and trenchant social commentary of one of the great works of the Enlightenment is restored and refreshed.

Voltaire may have cast a jaundiced eye on eighteenth-century Europe–a place that was definitely not the “best of all possible worlds.” But amid its decadent society, despotic rulers, civil and religious wars, and other ills, Voltaire found a mother lode of comic material. And this is why Peter Constantine’s thoughtful translation is such a pleasure, presenting all the book’s subtlety and ribald joys precisely as Voltaire had intended.

The globe-trotting misadventures of the youthful Candide; his tutor, Dr. Pangloss; Martin, and the exceptionally trouble-prone object of Candide’s affections, Cunégonde, as they brave exile, destitution, cannibals, and numerous deprivation, provoke both belly laughs and deep contemplation about the roles of hope and suffering in human life.

The transformation of Candide’s outlook from panglossian optimism to realism neatly lays out Voltaire’s philosophy–that even in Utopia, life is less about happiness than survival–but not before providing us with one of literature’s great and rare pleasures.

Die Inhaltsangabe kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Über die Autorin bzw. den Autor

Voltaire (François-Marie Arouet) (1694—1778) was one of the key thinkers of the European Enlightenment. Of his many works, Candide remains the most popular.

Peter Constantine was awarded the 1998 PEN Translation Award for Six Early Stories by Thomas Mann and the 1999 National Translation Award for The Undiscovered Chekhov: Forty-three New Stories. Widely acclaimed for his recent translation of the complete works of Isaac Babel, he also translated Gogol’s Taras Bulba and Tolstoy’s The Cossacks for the Modern Library. His translations of fiction and poetry have appeared in many publications, including The New Yorker, Harper’s, and Paris Review. He lives in New York City.

Von der hinteren Coverseite

A flamboyant and controversial personality of enormous wit and intelligence, Voltaire remains one of the most influential figures of the eighteenth-century Enlightenment. "Candide, his masterpiece, is a brilliant satire of the theory that our world is "the best of all possible worlds." The book traces the picaresque adventures of the guileless Candide, who is forced into the army, flogged, shipwrecked, betrayed, robbed, separated from his beloved Cunegonde, tortured by the Inquisition, et cetera, all without losing his resilience and will to live and pursue a happy life.

This Modern Library edition, published to celebrate the seventy-fifth anniversary of Random House,

is a facsimile of the first book ever released under the Random House colophon. It includes the timeless illustrations by Rockwell Kent, a twentieth-century artist whose wit and genius serve as a counterpart and compliment to Voltaire's.

"From the Hardcover edition.

Auszug. © Genehmigter Nachdruck. Alle Rechte vorbehalten.

CHAPTER I

How Candide was brought up in a beautiful castle, and how he was driven from it.

In the castle of Baron Thunder-ten-tronckh in Westphalia, there once lived a youth endowed by nature with the gentlest of characters. His soul was revealed in his face. He combined rather sound judgment with great simplicity of mind; it was for this reason, I believe, that he was given the name of Candide. The old servants of the household suspected that he was the son of the baron's sister by a good and honorable gentleman of the vicinity, whom this lady would never marry because he could prove only seventy-one generations of nobility, the rest of his family tree having been lost, owing to the ravages of time.

The baron was one of the most powerful lords in Westphalia, for his castle had a door and windows. Its hall was even adorned with a tapestry. The dogs in his stable yards formed a hunting pack when necessary, his grooms were his huntsmen, and the village curate was his chaplain. They all called him "My Lord" and laughed when he told stories.

The baroness, who weighed about three hundred fifty pounds, thereby winning great esteem, did the honors of the house with a dignity that made her still more respectable. Her daughter Cunegonde, aged seventeen, was rosy-cheeked, fresh, plump and alluring. The baron's son appeared to be worthy of his father in every way. The tutor Pangloss was the oracle of the household, and young Candide listened to his teachings with all the good faith of his age and character.

Pangloss taught metaphysico-theologo-cosmonigology. He proved admirably that in this best of all possible worlds, His Lordship's castle was the most beautiful of castles, and Her Ladyship the best of all possible baronesses.

"It is demonstrated," he said, "that things cannot be otherwise: for, since everything was made for a purpose, everything is necessarily for the best purpose. Note that noses were made to wear spectacles; we therefore have spectacles. Legs were clearly devised to wear breeches, and we have breeches. Stones were created to be hewn and made into castles; His Lordship therefore has a very beautiful castle: the greatest baron in the province must have the finest residence. And since pigs were made to be eaten, we eat pork all year round. Therefore, those who have maintained that all is well have been talking nonsense: they should have maintained that all is for the best."

Candide listened attentively and believed innocently, for he found Lady Cunegonde extremely beautiful, although he was never bold enough to tell her so. He concluded that, after the good fortune of having been born Baron Thunder-ten-tronckh, the second greatest good fortune was to be Lady Cunegonde; the third, to see her every day; and the fourth, to listen to Dr. Pangloss, the greatest philosopher in the province, and therefore in the whole world.

One day as Cunegonde was walking near the castle in the little wood known as "the park," she saw Dr. Pangloss in the bushes, giving a lesson in experimental physics to her mother's chambermaid, a very pretty and docile little brunette. Since Lady Cunegonde was deeply interested in the sciences, she breathlessly observed the repeated experiments that were performed before her eyes. She clearly saw the doctor's sufficient reason, and the operation of cause and effect. She then returned home, agitated and thoughtful, reflecting that she might be young Candide's sufficient reason, and he hers.

On her way back to the castle she met Candide. She blushed, and so did he. She greeted him in a faltering voice, and he spoke to her without knowing what he was saying. The next day, as they were leaving the table after dinner, Cunegonde and Candide found themselves behind a screen. She dropped her handkerchief, he picked it up; she innocently took his hand, and he innocently kissed hers with extraordinary animation, ardor and grace; their lips met, their eyes flashed, their knees trembled, their hands wandered. Baron Thunder-ten-tronckh happened to pass by the screen; seeing this cause and effect, he drove Candide from the castle with vigorous kicks in the backside. Cunegonde fainted. The baroness slapped her as soon as she revived, and consternation reigned in the most beautiful and agreeable of all possible castles.

CHAPTER II

What happened to Candide among the Bulgars.

After being driven from his earthly paradise, Candide walked for a long time without knowing where he was going, weeping, raising his eyes to heaven, looking back often toward the most beautiful of castles, which contained the most beautiful of young baronesses. He lay down without eating supper, between two furrows in an open field; it was snowing in large flakes. The next day, chilled to the bone, he dragged himself to the nearest town, whose name was Waldberghofftrarbk-dikdorff. Penniless, dying of hunger and fatigue, he stopped sadly in front of an inn. Two men dressed in blue1 noticed him.

"Comrade," said one of them, "there's a well-built young man who's just the right height."

They went up to Candide and politely asked him to dine with them.

"Gentlemen," said Candide with charming modesty, "I'm deeply honored, but I have no money to pay my share."

"Ah, sir," said one of the men in blue, "people of your appearance and merit never pay anything: aren't you five feet five?"

"Yes, gentlemen, that's my height," he said, bowing.

"Come, sir, sit down. We'll not only pay for your dinner, but we'll never let a man like you be short of money. Men were made only to help each other."

"You're right," said Candide, "that's what Dr. Pangloss always told me, and I see that all is for the best."

They begged him to accept a little money; he took it and offered to sign a note for it, but they would not let him. They all sat down to table.

"Don't you dearly love--"

"Oh, yes!" answered Candide. "I dearly love Lady Cunegonde."

"No," said one of the men, "we want to know if you dearly love the King of the Bulgars."

"Not at all," said Candide, "because I've never seen him."

"What! He's the most charming of kings, and we must drink to his health."

"Oh, I'll be glad to, gentlemen!"

And he drank.

"That's enough," he was told, "you're now the support, the upholder, the defender and the hero of the Bulgars: your fortune is made and your glory is assured."

They immediately put irons on his legs and took him to a regiment. He was taught to make right and left turns, raise and lower the ramrod, take aim, fire, and march double time, and he was beaten thirty times with a stick. The next day he performed his drills a little less badly and was given only twenty strokes; the following day he was given only ten, and his fellow soldiers regarded him as a prodigy.

Candide, utterly bewildered, still could not make out very clearly how he was a hero. One fine spring day he decided to take a stroll; he walked straight ahead, believing that the free use of the legs was a privilege of both mankind and the animals. He had not gone five miles when four other heroes, all six feet tall, overtook him, bound him, brought him back and put him in a dungeon. With proper legal procedure, he was asked which he would prefer, to be beaten thirty-six times by the whole regiment, or to receive twelve bullets in his brain. It did him no good to maintain that man's will is free and that he wanted neither: he had to make a choice. Using the gift of God known as freedom, he decided to run the gauntlet thirty-six times, and did so twice....

„Über diesen Titel“ kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Weitere beliebte Ausgaben desselben Titels

Suchergebnisse für Candide: or, Optimism (Modern Library Classics)

Candide: or, Optimism (Modern Library Classics)

Anbieter: World of Books (was SecondSale), Montgomery, IL, USA

Zustand: Good. Item in good condition. Textbooks may not include supplemental items i.e. CDs, access codes etc. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers 00099235681

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 2 verfügbar

Candide: or, Optimism (Modern Library Classics)

Anbieter: World of Books (was SecondSale), Montgomery, IL, USA

Zustand: Acceptable. Item in acceptable condition! Textbooks may not include supplemental items i.e. CDs, access codes etc. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers 00088842792

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 2 verfügbar

Candide: or, Optimism (Modern Library Classics)

Anbieter: Jenson Books Inc, Logan, UT, USA

paperback. Zustand: Very Good. A clean, cared for item that is unmarked and shows limited shelf wear. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers 4BQWN800421H

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Candide: or, Optimism (Modern Library Classics)

Anbieter: Wonder Book, Frederick, MD, USA

Zustand: Good. Good condition. A copy that has been read but remains intact. May contain markings such as bookplates, stamps, limited notes and highlighting, or a few light stains. Bundled media such as CDs, DVDs, floppy disks or access codes may not be included. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers H11I-00003

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Candide: or, Optimism (Modern Library Classics)

Anbieter: HPB Inc., Dallas, TX, USA

paperback. Zustand: Very Good. Connecting readers with great books since 1972! Used books may not include companion materials, and may have some shelf wear or limited writing. We ship orders daily and Customer Service is our top priority! Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers S_454668235

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Candide: or, Optimism (Modern Library Classics)

Anbieter: Half Price Books Inc., Dallas, TX, USA

Paperback. Zustand: Very Good. Connecting readers with great books since 1972! Used books may not include companion materials, and may have some shelf wear or limited writing. We ship orders daily and Customer Service is our top priority! Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers S_448240564

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Candide : Or, Optimism

Anbieter: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, USA

Zustand: Good. 1 Edition. Pages intact with minimal writing/highlighting. The binding may be loose and creased. Dust jackets/supplements are not included. Stock photo provided. Product includes identifying sticker. Better World Books: Buy Books. Do Good. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers 4717639-6

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 4 verfügbar

Candide : Or, Optimism

Anbieter: Better World Books: West, Reno, NV, USA

Zustand: Very Good. 1 Edition. Pages intact with possible writing/highlighting. Binding strong with minor wear. Dust jackets/supplements may not be included. Stock photo provided. Product includes identifying sticker. Better World Books: Buy Books. Do Good. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers 10846305-6

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Candide: or, Optimism (Modern Library Classics)

Anbieter: Magers and Quinn Booksellers, Minneapolis, MN, USA

paperback. Zustand: Very Good. May have light to moderate shelf wear and/or a remainder mark. Complete. Clean pages. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers 1229889

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Candide

Anbieter: GreatBookPrices, Columbia, MD, USA

Zustand: New. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers 3440972-n

Neu kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: Mehr als 20 verfügbar