Inhaltsangabe

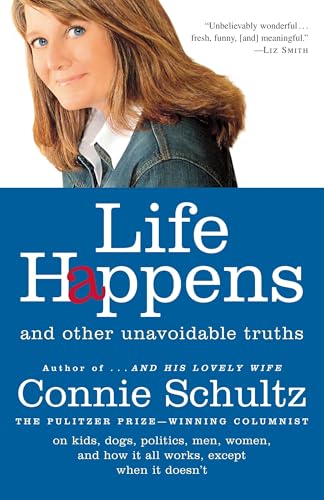

From the 2005 Pulitzer Prize—winning columnist Connie Schultz comes fresh, clever, insightful commentary on life today: love, politics, social issues, family, and much, much more. In the tradition of Anna Quindlen, Molly Ivins, and Erma Bombeck, but with a distinctive voice and sensibility all her own, Connie Schultz comes out of the heartland of America to get you seeing, feeling, and thinking more deeply about the lives we lead today.

“You might spot someone you know in the stories here,” writes Connie. “Maybe you’ll even find a glimpse of yourself. Yes, each of us is unique, but life happens in ways that bind us like Gorilla Glue.” In Life Happens, Connie shares sharp, passionate observations, winning our hearts with personal thoughts on a wide range of topics, from finding love in middle age to the meaning behind her father’s lunch pail, from single motherhood, to who really gets the tips you leave and why as the war in Iraq, race relations, gay marriage, and wwhy women

don’t vote. In a more humorous vein, Connie shares her mother’s advice on men (“Don’t marry him until you see how he treats the waitress”) and warns men everywhere against using the dreaded f-word (it’s not the one you think). Along the way, Connie introduces us to the heroic people who populate our world and shows us how just one person can make a difference.

Charming, provocative, funny, and perceptive, Life Happens gives us, for the first time, Connie Schultz’s celebrated commentary in one irresistible volume. Life Happens challenges us to be more open and alive to others and to the world around us.

Die Inhaltsangabe kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Über die Autorin bzw. den Autor

Connie Schultz, a bi-weekly columnist for the Cleveland Plain Dealer, won the Pulitzer Prize for Commentary in 2005. Her other accolades include the Scripps-Howard National Journalism Award, the National Headliner Award, the Batten Medal, and the Robert F. Kennedy Award for social-justice reporting. Her narrative series “The Burden of Innocence,” which chronicled the life of a man wrongly incarcerated for rape, was a Pulitzer Prize finalist. After the series ran, the real rapist turned himself in, and he is now serving a five-year prison sentence. vote. In a more humorous vein, Connie shares her mother’s advice on men (“Don’t marry him until you see how he treats the waitress”) and warns men everywhere against using the dreaded f-word (it’s not the one you think). Along the way, Connie introduces us to the heroic people who populate our world and shows us how just one person can make a difference.

Charming, provocative, funny, and perceptive, Life Happens gives us, for the first time, Connie Schultz’s celebrated commentary in one irresistible volume. Life Happens challenges us to be more open and alive to others and to the world around us.

Connie is married to Ohio’s popular congressman Sherrod Brown.

Auszug. © Genehmigter Nachdruck. Alle Rechte vorbehalten.

I grew up thinking you had to hate what you did for a living.

That single belief of my childhood probably explains more about who I am and how I became a writer than anything else I could tell you.

My first eighteen years were spent in a small Ohio town that most people passed through on their way to somewhere else. It’s called Ashtabula. You Bob Dylan fans may recall it was his creative reach for a rhyme to “Honolulu” in his song “You’re Gonna Make Me Lonesome When You Go.”

There are so many other towns just like Ashtabula all over the country. These towns are anonymous places where most of America does its living and dying. It’s funny, really, how much all of us, from big-city folks to little-town people, resemble one another at the end of the day. In my town we didn’t have Central Park or Hollywood Boulevard, but we did have the lady down the street leave her husband for her sister’s husband, and don’t even try telling me that isn’t the stuff of made-for-TV movies. Hubert Humphrey even visited our town once. Dad shook his hand and got him on a home movie, which we always watched right before the scene of me putting my doll in the toilet.

Without meaning to, my father taught me early that work was something you just had to put up with so you could enjoy the few hours you had left in any day, any life. He was one of those workers who showered at the end of the day, after his shift at the plant was done. For thirty-six years he worked for the local utility plant, and for thirty-six years he despised his job and what he was sure it said about him as a human being.

Most nights, Mom and all four of us kids would join Dad at the dinner table and, likely as not, he would tell another story from his day on the job. He included funny tales about coworkers and pleas for a different Hostess pie in his lunch pail, but mostly he talked about abusive supervisors and backbreaking work in temperatures that easily topped 100 degrees in the summer. He offered up his stories as mounting evidence of just how much he didn’t matter.

“Do you know what that bastard did to me today?” he’d say, not waiting for an answer before describing yet again how he was worse than invisible to the man ordering him around day in and day out.

“You kids are going to college,” he’d say, over and over. “You kids are going to be somebody.”

It was an order.

I am his oldest child, and over the years it grew harder and harder to watch that hurt masquerading as rage getting such a choke hold on my father’s view of himself and his life. He was my dad, the man I most respected and feared. He filled up our house in that way that ferocious men do, but he was nobody out there, in that hulking factory where he spent the bulk of his days and too many overtime nights.

I used to envy the bankers’ kids, the lawyers’ and doctors’ kids, even the kids whose dads were just insurance salesmen. I didn’t envy their fathers’ professions, just their access. Their fathers had offices their children could visit, secretaries and receptionists who would look up at them from tidy desks and say, “Your dad’s on the phone, honey. Have a seat until he waves you in.”

My dad worked in a place we could only see from the shores of Lake Erie. Sometimes, my mother would take us to a small patch of beach called Lake Shore Park. Gathering her chicks around her, she’d point to the smokestacks puffing huge gray clouds into the sky several miles away.

“Your daddy’s over there,” she’d yell. “Wave real hard and maybe he’ll see us.”

There we were, four skinny kids with the same bony knees, flapping and yelling, “Hi, Daddy!” as if he could actually hear us over the roar of the plant. One of those times, when I was about ten, I looked back at my mother as we hooted and hollered and saw that she wasn’t waving anymore. She just stood there, staring at those ugly smokestacks with a face I’d never seen her wear before. Through her eyes, I had just seen the enemy.

I never waved at the plant again.

Whenever my father talked about work at the dinner table, my mother would quietly listen, but the look on her face told me all I needed to know about what she was really thinking. Here was her big, burly husband, the only man she would ever love, and, oh, how she loved him, being mistreated in ways she would never visit on a dog. That’s a hard thing for a woman who loves her man, and I still wince at the memory of my tiny mother trying to lift up her fallen giant.

“They don’t know you like I know you,” she’d say, passing him a second helping of mashed potatoes, maybe asking if he’d like some canned peaches for dessert. I’m sure that, at such moments, there must have been an occasional look of tenderness between them, but I only remember my father staring straight ahead, his eyes narrowed in disbelief that this was his life.

At the beginning of my senior year, my high school guidance counselor, Joe Petro, asked me what I wanted to study in college. I’d never given it much thought, since all I really knew about college was what my parents told me: I had to go for four years, and I’d better have a job at the end.

“Well,” I said, “I thought I’d be a social worker.”

He frowned, shook his head. “I know you, Connie. You’ll burn out.”

He looked down at my test scores and tapped his finger on the page. “You’re good in English, and your writing scores are great. Have you ever thought of going into journalism?”

He looked at my blank face and smiled.

“You’re going to be working for a long time,” he said. “You’d better pick something you really like to do.”

Just like that, life happens: a sudden wide-awake flash changes, not just what you are, but who you are. Until that moment in Mr. Petro’s dingy office, it had never occurred to me that I could love what I do for a living. In an instant, there it was: my brand-new life.

Before I became a columnist, I was a reporter for more than twenty years. It was a career dug in the rich soil of other people’s lives, and that is fertile ground. Like many journalists, I am often asked how I get people to open up and talk so much, as if we keep some sort of magic dust in our pockets that we can scoop out and sprinkle around.

Truth be told, I spend a lot of time just paying attention. There are few people, indeed, who feel really heard on a regular basis. Who among us have enough people in our lives who hang on our every word, who know how life happened for us, and how it happens still? Good journalists ask great questions, but the best stories come about only when we shut up and listen. I haven’t met a person who doesn’t have at least one good tale, and if I leave an interview without hearing it, I always feel the blame is mine. Keeps the standard high.

All these years later, I still can’t quite believe I get paid to do this for a living. I left behind my working-class life, but its roots run long and deep, and they keep me tethered to values that steer my every step. While we’re clearly a country deeply divided, I find myself constantly stumbling onto common ground.

You might spot someone you know in the stories here. Maybe...

„Über diesen Titel“ kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Weitere beliebte Ausgaben desselben Titels

Suchergebnisse für Life Happens: And Other Unavoidable Truths

Life Happens: And Other Unavoidable Truths

Anbieter: World of Books (was SecondSale), Montgomery, IL, USA

Zustand: Good. Item in good condition. Textbooks may not include supplemental items i.e. CDs, access codes etc. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers 00097351624

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 2 verfügbar

Life Happens: And Other Unavoidable Truths

Anbieter: World of Books (was SecondSale), Montgomery, IL, USA

Zustand: Very Good. Item in very good condition! Textbooks may not include supplemental items i.e. CDs, access codes etc. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers 00098894657

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Life Happens: And Other Unavoidable Truths

Anbieter: BooksRun, Philadelphia, PA, USA

Paperback. Zustand: Good. Reprint. It's a preowned item in good condition and includes all the pages. It may have some general signs of wear and tear, such as markings, highlighting, slight damage to the cover, minimal wear to the binding, etc., but they will not affect the overall reading experience. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers 0812975685-11-1

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Life Happens: And Other Unavoidable Truths

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Phoenix, Phoenix, AZ, USA

Paperback. Zustand: Very Good. No Jacket. May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers G0812975685I4N00

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Life Happens: And Other Unavoidable Truths

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Reno, Reno, NV, USA

Paperback. Zustand: Very Good. No Jacket. May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers G0812975685I4N00

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Life Happens: And Other Unavoidable Truths

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Dallas, Dallas, TX, USA

Paperback. Zustand: Good. No Jacket. Pages can have notes/highlighting. Spine may show signs of wear. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers G0812975685I3N00

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Life Happens: And Other Unavoidable Truths

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Dallas, Dallas, TX, USA

Paperback. Zustand: Very Good. No Jacket. May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers G0812975685I4N00

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 2 verfügbar

Life Happens: And Other Unavoidable Truths

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Atlanta, AUSTELL, GA, USA

Paperback. Zustand: Very Good. No Jacket. May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers G0812975685I4N00

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 2 verfügbar

Life Happens : And Other Unavoidable Truths

Anbieter: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, USA

Zustand: Good. Pages intact with minimal writing/highlighting. The binding may be loose and creased. Dust jackets/supplements are not included. Stock photo provided. Product includes identifying sticker. Better World Books: Buy Books. Do Good. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers 973474-6

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Life Happens : And Other Unavoidable Truths

Anbieter: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, USA

Zustand: Very Good. Pages intact with possible writing/highlighting. Binding strong with minor wear. Dust jackets/supplements may not be included. Stock photo provided. Product includes identifying sticker. Better World Books: Buy Books. Do Good. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers 973476-6

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 2 verfügbar