Inhaltsangabe

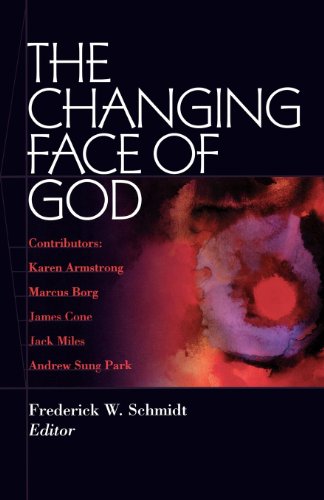

In 1999, five scholars presented lectures at Washington National Cathedral about our images of God and what difference they make. This book is ideal for parish study groups and individuals to consider and discuss the viewpoints of Marcus Borg, Karen Armstrong, Jack Miles, James Cone, and Andrew Sung Park.

"Does the face of God change? Years ago I would have said, 'No.' Countless hymns, passage of Scripture and confessions of faith assert or imply the changelessness of God. To take issue with traditions that are centuries, if not millennia old, seemed to be daunting and misguided....But when the great professions of confidence in God harden into philosophical propositions, one is bound to ask: What difference would it make to say that God has only one face? Even if true in some sense, the fact of the matter is that features each of us would count as necessary and changeless would be a matter of considerable debate."

- From the Introduction

Die Inhaltsangabe kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Über die Autorin bzw. den Autor

Frederick W. Schmidt is an Episcopal priest and the Rueben P. Job Chair in Spiritual Formation at Garrett-Evangelical Theological Seminary in Evanston, Illinois. He is the author of several books, including "The Dave Test: A Raw Look at Real Faith in Hard Times."

Auszug. © Genehmigter Nachdruck. Alle Rechte vorbehalten.

THE CHANGING FACE OF GOD

By Karen Armstrong, MARCUS J. BORG, James H. Cone, Jack Miles, Andrew Sung Park, Frederick W. SchmidtChurch Publishing Incorporated

All rights reserved.

Contents

| CHAPTER ONE THE CHANGING FACE OF GOD Frederick W. Schmidt | |

| CHAPTER TWO THE GOD OF IMAGINATIVE COMPASSION Karen Armstrong | |

| CHAPTER THREE THE GOD WHO IS SPIRIT Marcus J. Borg | |

| CHAPTER FOUR GOD IS THE COLOR OF SUFFERING James H. Cone | |

| CHAPTER FIVE A COMPLICATED GOD Jack Miles | |

| CHAPTER SIX THE GOD WHO NEEDS OUR SALVATION Andrew Sung Park | |

| SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY | |

| FOR FURTHER READING |

CHAPTER 1

THE CHANGING FACE OF GOD

Frederick W. Schmidt

Does the face of God change? Years ago I would have said, "No." Countless hymns,passages of Scripture, and confessions of faith assert or imply thechangelessness of God. To take issue with traditions that are centuries, if notmillennia old, seemed to be both daunting and misguided.

I eventually realized, however, that many of these great professions of faithwere bent on underlining the reliability of God. Both their theological andsocial function was to reassure believers of divine trustworthiness. To takethem as flat assertions of fact would be as wrongheaded as the attempt to takethe words of a poet in literal terms.

Nonetheless, it is true that some of those great statements of faith are meantto convey just exactly what they appear to convey. God never changes. So why thequestion?

Well, for one thing, there is a difference between the assertion that God neverchanges and the assertion that our perception of God—our view of God's "face"—neverchanges. The former is an assertion that God's nature has a permanenceabout it that nothing else around us can claim, an "immutability," theologianscall it. The latter is a very different kind of statement. Like the elephant ofthe great Indian proverb that each blind man touches, our perceptions alter aswe move from leg to trunk and from trunk to ear. In other words, the reality ofGod is large enough that, even in traditional terms, one could argue that God'sface changes as we learn more, seeing now this feature and then another.

But then when the great professions of confidence in God harden intophilosophical propositions, one is bound to ask, "What difference would it maketo say that God has only one face?" Even if true in some sense, the fact of thematter is that the features each of us would count as necessary and changelesswould be a matter of considerable debate. In fact, much of the history of boththeology and the life of the church is about those differences. We could evensay that the conversation about the changing face of God is not only under way,the church has actually embraced and memorialized the conversation in stone.

The Church of the Annunciation in northern Galilee is an excellent example ofthe potential diversity. It sits atop the remains of the hamlet that was oncebiblical Nazareth. Devoted to Mary, the Mother of Jesus, the church boasts aseries of Madonnas donated by Christians from around the world. Mother and childare sharply distinguished by the culture, aesthetic, and skin color of eachdonor-nation. The Madonna and Child given by Sierra Leone features costumes andiconography of one kind. The figures designed in Japan feature another, drawingon an artistic style characteristic of an earlier century. And the image of Marydonated by the United States is dressed in a flowing, metallic robe that hasprompted some visitors to draw comparison with aluminum foil!

It takes very little time to realize that even the diversity of theseinterpretations obscures the endless variety that lies behind the representativework of the artists. Not all Americans would choose to evoke the associationsthat accompany the heavy folds of Mary's metallic dress, and we can safely saythat the aesthetic assumptions that shape the faith and imagination of allJapanese Christians are hardly captured in the work of their own artist.

What is undeniably true, although difficult to remember, is that the sameassumptions shape more than our canons of beauty. They shape and define ourunderstanding of the truth, they determine what we believe to be important, andas a consequence, those assumptions give each of our lives a radically differentshape.

Not all of even the most important differences arise out of our nationalidentity. Race, socioeconomic status, education, and the vagaries of life givean added shape and texture to our view of the world around us.

In the final analysis, the resulting diversity is not the surprise. The surpriseis the extent to which we share a common bond or manage to communicate around,through, and over the differences. I can still remember a dear Jamaican friendof mine who studied for a time in Chicago noting that theologians thereregularly debated issues that were of little or no significance for his owncountry. The space that wealth created for one kind of dialogue was all butimpossible in a country laboring under the burden of poverty.

This, then, is why the assertion that the face of God is unchanging has limitedutility, even though it might have philosophical merit. And yet, it has heldsway, lending our conversation about God a "given-ness" that we are rarelywilling to probe. As a result, we overlook, ignore, and suppress the vital rolethat our education and experience play in shaping our view of God. And, yet, ifwe probed them, I suspect that the differences would far outnumber our personalpictures of Madonna and Child!

There are a number of reasons for our failure to confront this reality. For someof us the task of examining the differences is simply too demanding. Modern lifemakes demands on our time and energies that exceed the ability of those who donot specialize in theology, just as surely as the demands of still otherdisciplines (e.g., quantum physics) exceed the theologian's. So in our franticsearch for at least a few fixed assumptions (or ones that we just don'texamine), our assumptions about God are as good or better than any others. Theyappear to impinge less immediately on our lives, and frankly, it's comforting tomake assumptions about God.

But it's that last observation about comfort that hints at still anotherobstacle: the structure of our faith itself. Years ago, as I began teachingbiblical studies, I attempted to understand the almost violent reaction that afew of my students had to any of my attempts to teach them—almost anything—aboutthe biblical text. Even my deliberate attempts to pick the simplest illustrationof a point failed to win concessions from them on which I could base my largerobservations.

I soon realized that in large part their resistance to any new informationrested on the structure of their faith. Convinced that this or that assumptionabout the Bible was true, they believed that faith in God was also viable. Inother words, they entertained faith in an ultimate authority because they hadfaith in proximate authorities. However gently you challenged their assumptionsabout the Bible, you effectively challenged their ability to believe in God atall. Now imagine asking anyone more directly to grapple with their understandingof God—the changing face of God. The level of resistance is predictable.

Finally, I think it's also fair to say that we grow up with a number ofassumptions about God and our world that are left unexamined unlesscircumstances demand that we take a second look. I can still remember a dearfriend's note when I landed my first stateside teaching job: "Dear Fred,Congratulations on securing a teaching post. I hope you have time to read andreflect!" We live in what one writer has described as an "unconsciouscivilization," and the pace of life has narrowed the number of basic questionswe are willing to ask ourselves as we hurry along to meet the latest challenge.The acquisition of wisdom has given way to the acquisition of apparentlynecessary, but also readily disposable knowledge. And it is often only inmoments of crisis that we reexamine something like our assumptions about thenature of God.

Having said that, if you have the energy, I'd like to suggest that there isstill another very good reason for raising the opening question: the changingshape of the world in which we live.

Trace the realization to our relative place in the scheme of things, or trace itto the sheer speed with which our world is changing, there is little doubt thatwe are living in an era marked by new intellectual and spiritual demands. If theworld we have inherited was ruled by a God who reigned over an era marked by"the domination of nature, the primacy of method, and the sovereignty of theindividual," today that is no longer the case. If God ruled that world in acertain degree of splendid isolation from the gods of other religions, that toois a matter of history. And if science seemed to allow for a clock-maker-Godwho was deeply involved in the world's creation and remote from its day-to-daymaintenance, the modern version of the same scientific endeavor now seems tocall for a God who is both more removed from the world and more intimatelyinvolved in it than we once thought.

And so, the opening question. What is stunning is that the question is beingasked by so many people. There was a time not too long ago when theologians werein a hasty retreat from the genuinely big, synthetic questions. The sociologyof graduate education wed with the demise of (often German) schools of thoughtdrove scholars back to the narrow specializations that had earned them theirhighest academic honors. Even those explicitly charged with the big, synthetictask preferred to write "overtures" to one kind of theology or another, ratherthan tackle theology itself.

Now, however, a growing number of scholars are addressing the biggest questionof all: who is God? Some of them are members of the guild, some of them live onits fringes. Some of them are deeply involved in the life of the church, someare not. But all of them are writing for audiences beyond the walls of theacademy.

Borrowing a term from the study of the historical Jesus, one could almost speakof "the new quest for God." But it would be a mistake to describe that quest innarrow terms. The architects of this new quest are as diverse in their approachto the subject as they are in their experience and expertise.

Some, like Marcus Borg, are engaged in recapturing emphases that have theirorigins in Christian theology, but which have slipped (or were pushed!) from thetheological bandwagon as it made its way over the centuries. As familiar as sheis with this material, Karen Armstrong searches the deepest commonalties thatChristianity shares with Judaism and Islam. Singling out the Jewish experience,Jack Miles probes the complex picture offered by the Hebrew Bible, allowing eachelement to be seen on its own terms, resisting the temptation to homogenize thewhole in a way that dispels the differences and tensions. No less familiarwith the theological heritage of the church, James Cone begins with the blackexperience, arguing that there is something seminal in the experience ofoppression that cannot be omitted from the theological equation. And drawingon a completely different set of experiences, Andrew Sung Park draws on thefresh voice of Asian and, specifically, Korean Christianity as a means ofsupplying nuances largely missing from Western theological vocabulary.

Their work and the work of others constitutes a new theological and intellectualmovement that takes up where the so-called Death of God discussion left off andcan be seen as a part of the unfinished theological agenda of the twentiethcentury. Even then it was quite clear that there was a growing consensus thatour theological categories required careful scrutiny and candid dialogue.Unfortunately the debate was popularized at the expense of nuance (as it sooften is) and what had been advanced as a call for judicious review was castinstead in a choice for or against faith in God's existence, just as the phrase"Death of God" suggests. The conversation was quickly reduced to the length of abumper sticker ("My God is alive, sorry to hear about yours!") and theopportunity was largely, though not completely, lost.

Where the current round of contributions and others like it will take us isdifficult to say. The process of popularization continues to be among thegreatest enemies of nuance and the closing decade of the last century was markedby growing incivility that suggests the dialogue may not be any easier tosustain now than it was then.

As the German theologian Hans Küng has observed, however, "New models oftheological interpretation do not simply come into existence because individualtheologians tackle heated issues or sit down at their desks to construct newmodels, but because the traditional interpretive model has failed, because the'problem solvers' of normal theology, in the face of a changed historicalhorizon, can find no satisfying answers for new major questions, and 'paradigmtesters' set in motion a 'extra-ordinary theology' alongside the normalvariety." Borg, Armstrong, Miles, Cone, and Park are among the "paradigmtesters."

Just exactly what theological change will look like in the future, however, isnow in considerable debate. At one point in history, the church in the West wasthe architect of theological pronouncements for the Latin and Protestanttraditions. The content of faith was something that European and Americanchurches largely "exported" to other parts of the world. For that reasonchanges in the West dictated the shape of theology for much of the church, andalthough theology has always been subject to more than simply the intellectualforces requisite for its change, change remained a simpler process because itengaged people on a smaller social and cultural front.

That is no longer the case, and recent encounters between the church of thenorthern and southern hemispheres have brought the differences in our social,cultural, and theological horizons into sharp relief. Witness, for example, thedebate at Lambeth between the bishops of the larger Anglican communion and thebishops of North America.

The changes are not all abroad, however. New complexities exist here in theUnited States as well. The old formulations that served as a map for much ofwhat we took as the theological world in which we live will hardly serve thepurpose any longer. Driving through America's heartland between Detroit,Michigan, and Dayton, Ohio, you will pass churches of every known denomination,but you will also pass independent churches, each with a different andidiosyncratic name. And then, on an otherwise rural horizon a minaret will riseabove the flatlands of Ohio. Add to this the increasingly individualistic andeclectic character of American spiritual pursuits that are without attachment toan institution of any kind and it becomes clear that theological consensus is afar harder thing to achieve than it was in the first half of the twentiethcentury.

The European and American scenes, are not so deeply connected as they once were.There was a time when the leading theologians in the United States were trainedin England and Germany. A common vocabulary and, to some extent, a commontheological agenda existed as a result. That is no longer the case, and Americantheology has assumed an indigenous character all its own, while Europeantheologians have continued to go their own way.

The point is this: If theological change has always been dependent on more thanthe intellectual requirements for transformation, that process is now imbeddedin a far more complex setting in which the intellectual requirements are evenless decisive than they once were. As a result, change is likely to be adisparate, regional process that responds as much to social, cultural, andeconomic differences as almost anything else.

In addition, theological dialogue over, around, and through those differences islikely to be sporadic, disconnected, and awkward. Indeed, the key to any successin attempting to move collectively along a given front will rest heavily on theability of all parties to move beyond the language of colonialism andimperialism, acknowledging that the theological agendas of each hemisphere, ifnot each country, are likely to be radically different for some time to come.

If theology is a quest for the "truth," however, then the quest itself cannotwait for either regional or global transformations. Nor will anyone alive to theissues outlined above find it appealing to wait for the larger consensus thatmay or may not be in the making. Theology requires personal appropriation; andif the highly individual character of American religious life has made thedevelopment of consensus more difficult, the same individualistic bent has madethe personal discovery of a satisfactory vision of God all the more imperative.

Exactly the shape this process of discovery will take is, of course, equallydifficult to say. And, as I've already noted, it is a process that can engenderenormous fear and misgiving among far more than just college freshmen.Nonetheless, it should be a task that we embrace more self-consciously—buildinga bigger conceptual box—discovering a vision of God that is marked by greateradequacy. Call the results a theology of God, a paradigm, or a mental model, ourpictures of God are and should be forever provisional, shifting to meet bothnarrower and larger needs, grasping more of the nature of God on some level,while at the same time acknowledging that they are less than can ever be known.

(Continues...)

Excerpted from THE CHANGING FACE OF GOD by Karen Armstrong, MARCUS J. BORG, James H. Cone, Jack Miles, Andrew Sung Park, Frederick W. Schmidt. Copyright © 2000 The Protestant Episcopal Cathedral Foundation of the District of Columbia. Excerpted by permission of Church Publishing Incorporated.

All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Excerpts are provided by Dial-A-Book Inc. solely for the personal use of visitors to this web site.

„Über diesen Titel“ kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Suchergebnisse für The Changing Face of God

The Changing Face of God

Anbieter: World of Books (was SecondSale), Montgomery, IL, USA

Zustand: Good. Item in good condition. Textbooks may not include supplemental items i.e. CDs, access codes etc. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers 00083137934

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 4 verfügbar

The Changing Face of God

Anbieter: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, USA

Zustand: Good. Former library book; may include library markings. Used book that is in clean, average condition without any missing pages. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers GRP96132674

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

The Changing Face of God

Anbieter: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, USA

Zustand: Good. Used book that is in clean, average condition without any missing pages. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers 5658231-6

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 2 verfügbar

The Changing Face of God

Anbieter: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, USA

Zustand: Very Good. Used book that is in excellent condition. May show signs of wear or have minor defects. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers 5699071-6

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

The Changing Face of God

Anbieter: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, USA

Zustand: Very Good. Former library book; may include library markings. Used book that is in excellent condition. May show signs of wear or have minor defects. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers 7685656-6

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

The Changing Face of God

Anbieter: Once Upon A Time Books, Siloam Springs, AR, USA

paperback. Zustand: Good. This is a used book in good condition and may show some signs of use or wear . This is a used book in good condition and may show some signs of use or wear . Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers mon0001299093

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

The Changing Face of God

Anbieter: Red's Corner LLC, Tucker, GA, USA

paperback. Zustand: Good. All orders ship by next business day! This is a used paperback book. Has moderate wear on cover and/or pages. Has markings on pages. Spine has been opened/creased. For USED books, we cannot guarantee supplemental materials such as CDs, DVDs, access codes and other materials. We are a small company and very thankful for your business! Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers 4CNO3I0026W7

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

The Changing Face of God

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Dallas, Dallas, TX, USA

Paperback. Zustand: Very Good. No Jacket. May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers G0819218014I4N00

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

The Changing Face of God

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Atlanta, AUSTELL, GA, USA

Paperback. Zustand: Good. No Jacket. Pages can have notes/highlighting. Spine may show signs of wear. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers G0819218014I3N00

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

The Changing Face of God

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Dallas, Dallas, TX, USA

Paperback. Zustand: Good. No Jacket. Pages can have notes/highlighting. Spine may show signs of wear. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers G0819218014I3N00

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar