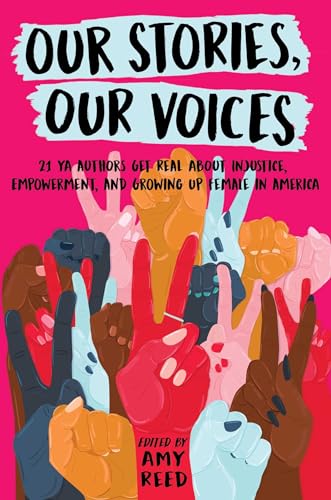

Our Stories, Our Voices: 21 YA Authors Get Real About Injustice, Empowerment, and Growing Up Female in America - Hardcover

Inhaltsangabe

From Amy Reed, Ellen Hopkins, Amber Smith, Sandhya Menon, and more of your favorite YA authors comes an anthology of essays that explore the diverse experiences of injustice, empowerment, and growing up female in America.

This collection of twenty-one essays from major YA authors—including award-winning and bestselling writers—touches on a powerful range of topics related to growing up female in today’s America, and the intersection with race, religion, and ethnicity. Sure to inspire hope and solidarity to anyone who reads it, Our Stories, Our Voices belongs on every young woman’s shelf.

This anthology features essays from Martha Brockenbrough, Jaye Robin Brown, Sona Charaipotra, Brandy Colbert, Somaiya Daud, Christine Day, Alexandra Duncan, Ilene Wong (I.W.) Gregorio, Maurene Goo. Ellen Hopkins, Stephanie Kuehnert, Nina LaCour, Anna-Marie LcLemore, Sandhya Menon, Hannah Moskowitz, Julie Murphy, Aisha Saeed, Jenny Torres Sanchez, Amber Smith, and Tracy Deonn.

Die Inhaltsangabe kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Über die Autorinnen und Autoren

Amy Reed is the author of the contemporary young adult novels Beautiful, Clean, Crazy, Over You, Damaged, Invincible, Unforgivable, The Nowhere Girls, and The Boy and Girl Who Broke the World. She is also the editor of Our Stories, Our Voices. She is a feminist, mother, and quadruple Virgo who enjoys running, making lists, and wandering around the mountains of western North Carolina where she lives. You can find her online at AmyReedFiction.com.

Sandhya Menon is the New York Times bestselling author of When Dimple Met Rishi, Of Curses and Kisses, and many other novels that also feature lots of kissing, girl power, and swoony boys. Her books have been included in several cool places, including Today, Teen Vogue, NPR, BuzzFeed, and Seventeen. A full-time dog servant and part-time writer, she makes her home in the foggy mountains of Colorado. Visit her online at SandhyaMenon.com.

Ellen Hopkins is the #1 New York Times bestselling author of numerous young adult novels, as well as the adult novels such as Triangles, Collateral, and Love Lies Beneath. She lives with her family in Carson City, Nevada, where she has founded Ventana Sierra, a nonprofit youth housing and resource initiative. Follow her on Twitter at @EllenHopkinsLit.

Amber Smith is the New York Times, USA TODAY, and internationally bestselling author of the young adult novels The Way I Used to Be, The Last to Let Go, Something Like Gravity, and The Way I Am Now. An advocate for increased awareness of gendered violence and LGBTQIA+ equality, she writes in the hope that her books can help foster change and spark dialogue. She lives in Ithaca, New York, with her wife and coauthor, Sam Gellar, and their ever-growing family of rescued dogs and cats. You can find her online at AmberSmithAuthor.com.

Stephanie Kuehnert got her start writing bad poetry about unrequited love and razor blades in eighth grade. In high school, she discovered punk rock and produced several D.I.Y. feminist zines. She received her MFA in creative writing from Columbia College Chicago and lives in Seattle, Washington. She is the author of Ballads of Surburbia and I Wanna Be Your Joey Ramone. Learn more at StephanieKuehnert.com.

Auszug. © Genehmigter Nachdruck. Alle Rechte vorbehalten.

My Immigrant American Dream MY IMMIGRANT AMERICAN DREAM Sandhya Menon

My first night in America was a sleepless one spent wide-eyed in the dark, listening to the crushing silence. This is going to be great, I promised my fifteen-year-old self. You’re going to love it here.

My family and I had just moved to Charleston, South Carolina, from Mumbai (Bombay), India. We’d moved periodically between India and the United Arab Emirates before, but I’d always lived an insulated life in the Middle East, studying at Indian schools and engaging mainly with the very large Indian community there. This, being plunged into a brand-new culture in a brand-new country where the population of Indians wasn’t nearly as numerous, was completely novel. The lack of noisy, bustling rickshaws and street vendors hawking glass bangles and multicolored saris would take some getting used to. But the thing I had to get used to the most was being an outsider in a country of outsiders.

I’d heard from excited friends and relatives that America was the land of immigrants. “Even the white people who are the majority there are actually immigrants, if you look at their ancestors!” people told me. “Plus, Americans love people who are different. Just look at San Francisco.” We knew many friends who had immigrated to America, whose children were born there, and the stories that trickled home were dotted with details that made me salivate: convertible cars and spotless beaches, people who dressed like Westerners in short-shorts and tank tops. Besides, America was famous for its equal treatment of women. India still had huge strides to make in that arena when I lived there, and I was eager for a change. I was so ready to be welcomed with open arms, to make exotic American friends who might grow to love Bollywood movies and Hindi songs like I did.

What happened was a little less idyllic. I had a thick Indian accent when I first moved to the States, and people—including some teachers at my small magnet school—immediately thought that meant I couldn’t speak English, period. By then I’d already had short stories (written in English) published in international magazines, so that wasn’t the case at all. There were also other micro- and macroaggressions to get used to, ones I wasn’t expecting from the land of immigrants.

I distinctly remember my father speaking to store clerks who would sigh and roll their eyes because they couldn’t understand him. They spoke slowly and loudly, as if he—a highly educated engineer who’d lived all over the world—were having trouble understanding them. Occasionally I was stopped in my neighborhood by the police and asked what I was doing there, whether I was in the country legally, and where I lived. As far as I could tell, the only reason I was stopped was because of the color of my skin. My friend who’d emigrated from Russia the same year as me reported never having experienced that particular form of harassment. One boy insisted on sneeringly calling me Ganesh in class because of the religion my parents practiced, and the teacher never stepped in. At the post office someone yelled at me and my mom to go back to our country because, apparently, we were standing in line wrong. I got used to the question, asked seemingly casually but with a gimlet eye: “Are you here legally?” whenever I said I didn’t have a social security number, since I was here as a dependent on my dad’s work visa. It made my cheeks burn at first. My parents had paid a lot of money to come to the States; we’d gone through all the proper channels and jumped through all the hoops (and of those there were many). What right did they have to ask me that when they didn’t even know how visas worked, when many of them had never even been out of this country? And anyway, what did they think? That I swam all the way from India?

Not all experiences were negative, however. I did enjoy greater gender equality in the United States than I had in India. Egalitarian messages pervaded my high school: we were told we could do anything a boy could do, be anything a boy could be. Still, these messages were implicitly and explicitly targeted at white girls and women. The role models and those they spoke to looked nothing like me.

For the longest time I thought there must be something wrong with me for people—even people I respected or considered my friends—to say the things I was hearing. Once I realized I was accepted as a woman, just not as an immigrant, I figured I needed to acculturate better. The other Indian kids around me, the ones who seemed to be accepted, at least to my eye, seemed indistinguishable in accent and dress from the American kids. (At the time I didn’t get the concept of Indian-Americanness.) So I began to speak with an American accent. I tried to blend in so much that I would actively decry Indian things. When people asked me about arranged marriage I would announce that I didn’t believe in it. When people asked if I spoke Hindi, I automatically said, “Yes, but I speak English better and it was my first language.” I began to shop at Old Navy whenever my parents would let me, and I relegated all my Indian clothes to the back of my closet.

One of the biggest losses, though, was my art. Although I still wrote in a private journal, my stories and drawings began to go by the wayside. I refused to let people peek into my imagination. I didn’t know what was “acceptable” anymore, so I simply stopped creating. I was, without thinking, trying to obliterate those parts of myself that I thought weren’t American enough (and to me, in those days, “American” meant “white” because that’s the message I was getting). I wanted to be lighter skinned, taller. I wanted to blend in and become someone else. I was trying to perfect the art of becoming the human chameleon.

But as I went through high school and then college, a strange and wonderful thing started to happen. I began to see myself for who I was, past all the cladding of “immigrant versus American born,” of “accent versus no accent.” There was a side to me, I realized, that had nothing to do with the labels other people gave me. I started to pay attention to that side more, to unearth who I was for myself.

My volunteering with the teen crisis line and individuals with developmental disabilities, for instance, helped me see I was a person capable of empathy and kindness. My high school best friend, who happened to be the daughter of Nigerian immigrants, helped me see that there was nothing inherently wrong with being an immigrant. She embraced her Nigerian roots and celebrated her parents’ accent and where they’d come from. The way she spoke openly about the injustices they faced helped me see that that’s what they were—injustices, prejudice, ignorance. I’d had a hard time seeing it when it was directed at me, but seeing it directed at a friend drew the line between right and wrong pretty starkly.

I met incredible women in the places where I volunteered, who told stories of overcoming traumatic pasts and abusive partners, mental illness and poverty. We had a mutual sense of responsibility to share what resources we now had with others less fortunate. We spoke about what it meant to be female, how easy it was to be hurt, but how capable we were of healing.

I enjoyed the freedom of being able to walk down the street without...

„Über diesen Titel“ kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Weitere beliebte Ausgaben desselben Titels

Suchergebnisse für Our Stories, Our Voices: 21 YA Authors Get Real About...

Our Stories, Our Voices: 21 YA Authors Get Real About Injustice, Empowerment, and Growing Up Female in America

Anbieter: World of Books (was SecondSale), Montgomery, IL, USA

Zustand: Good. Item in good condition. Textbooks may not include supplemental items i.e. CDs, access codes etc. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers 00084561918

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 2 verfügbar

Our Stories, Our Voices: 21 YA Authors Get Real About Injustice, Empowerment, and Growing Up Female in America

Anbieter: World of Books (was SecondSale), Montgomery, IL, USA

Zustand: Very Good. Item in good condition. Textbooks may not include supplemental items i.e. CDs, access codes etc. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers 00060069873

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 2 verfügbar

Our Stories, Our Voices: 21 YA Authors Get Real About Injustice, Empowerment, and Growing Up Female in America

Anbieter: More Than Words, Waltham, MA, USA

Zustand: Good. . . All orders guaranteed and ship within 24 hours. Before placing your order for please contact us for confirmation on the book's binding. Check out our other listings to add to your order for discounted shipping. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers WAL-T-2c-01864

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Our Stories, Our Voices: 21 YA Authors Get Real About Injustice, Empowerment, and Growing Up Female in America

Anbieter: Once Upon A Time Books, Siloam Springs, AR, USA

hardcover. Zustand: Acceptable. This is a used book. It may contain highlighting/underlining and/or the book may show heavier signs of wear . It may also be ex-library or without dustjacket. This is a used book. It may contain highlighting/underlining and/or the book may show heavier signs of wear . It may also be ex-library or without dustjacket. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers mon0003347186

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Our Stories, Our Voices : 21 YA Authors Get Real about Injustice, Empowerment, and Growing up Female in America

Anbieter: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, USA

Zustand: Good. Former library copy. Pages intact with minimal writing/highlighting. The binding may be loose and creased. Dust jackets/supplements are not included. Includes library markings. Stock photo provided. Product includes identifying sticker. Better World Books: Buy Books. Do Good. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers 17823671-6

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 2 verfügbar

Our Stories, Our Voices : 21 YA Authors Get Real about Injustice, Empowerment, and Growing up Female in America

Anbieter: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, USA

Zustand: Good. Pages intact with minimal writing/highlighting. The binding may be loose and creased. Dust jackets/supplements are not included. Stock photo provided. Product includes identifying sticker. Better World Books: Buy Books. Do Good. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers 16545415-6

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Our Stories, Our Voices : 21 YA Authors Get Real about Injustice, Empowerment, and Growing up Female in America

Anbieter: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, USA

Zustand: Very Good. Former library copy. Pages intact with possible writing/highlighting. Binding strong with minor wear. Dust jackets/supplements may not be included. Includes library markings. Stock photo provided. Product includes identifying sticker. Better World Books: Buy Books. Do Good. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers 18004433-6

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Our Stories, Our Voices: 21 YA Authors Get Real About Injustice, Empowerment, and Growing Up Female in America

Anbieter: The Maryland Book Bank, Baltimore, MD, USA

hardcover. Zustand: Like New. Used - Like New. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers 3-NNN-2-0243

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Our Stories, Our Voices: 21 YA Authors Get Real about Injustice, Empowerment, and Growing Up Female in America

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Dallas, Dallas, TX, USA

Hardcover. Zustand: Very Good. No Jacket. Former library book; May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers G1534408991I4N10

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Our Stories, Our Voices: 21 YA Authors Get Real about Injustice, Empowerment, and Growing Up Female in America

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Atlanta, AUSTELL, GA, USA

Hardcover. Zustand: Very Good. No Jacket. Former library book; May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers G1534408991I4N10

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar