Inhaltsangabe

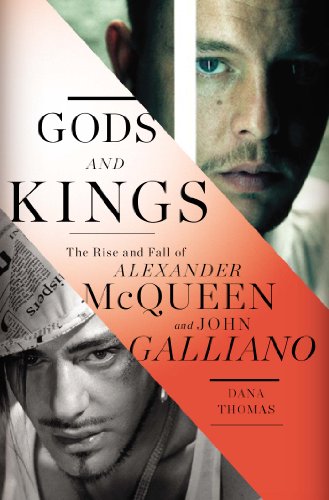

More than two decades ago, John Galliano and Alexander McQueen arrived on the fashions scene when the business was in an artistic and economic rut. Both wanted to revolutionize fashion in a way no one had in decades. They shook the establishment out of its bourgeois, minimalist stupor with daring, sexy designs. They turned out landmark collections in mesmerizing, theatrical shows that retailers and critics still gush about and designers continue to reference.

Their approach to fashion was wildly different—Galliano began as an illustrator, McQueen as a Savile Row tailor. Galliano led the way with his sensual bias-cut gowns and his voluptuous hourglass tailoring, which he presented in romantic storybook-like settings. McQueen, though nearly ten years younger than Galliano, was a brilliant technician and a visionary artist who brought a new reality to fashion, as well as an otherworldly beauty. For his first official collection at the tender age of twenty-three, McQueen did what few in fashion ever achieve: he invented a new silhouette, the Bumster.

They had similar backgrounds: sensitive, shy gay men raised in tough London neighborhoods, their love of fashion nurtured by their doting mothers. Both struggled to get their businesses off the ground, despite early critical success. But by 1997, each had landed a job as creative director for couture houses owned by French tycoon Bernard Arnault, chairman of LVMH.

Galliano’s and McQueen’s work for Dior and Givenchy and beyond not only influenced fashion; their distinct styles were also reflected across the media landscape. With their help, luxury fashion evolved from a clutch of small, family-owned businesses into a $280 billion-a-year global corporate industry. Executives pushed the designers to meet increasingly rapid deadlines. For both Galliano and McQueen, the pace was unsustainable. In 2010, McQueen took his own life three weeks before his womens' wear show.

The same week that Galliano was fired, Forbes named Arnault the fourth richest man in the world. Two months later, Kate Middleton wore a McQueen wedding gown, instantly making the house the world’s most famous fashion brand, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art opened a wildly successful McQueen retrospective, cosponsored by the corporate owners of the McQueen brand. The corporations had won and the artists had lost.

In her groundbreaking work Gods and Kings, acclaimed journalist Dana Thomas tells the true story of McQueen and Galliano. In so doing, she reveals the revolution in high fashion in the last two decades—and the price it demanded of the very ones who saved it.

Die Inhaltsangabe kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Über die Autorinnen und Autoren

Dana Thomas is the author of the New York Times bestseller Deluxe: How Luxury Lost Its Luster. She began her career writing for the “Style” section of The Washington Post, and for fifteen years she served as the European cultural and fashion correspondent for Newsweek in Paris. She is currently a contributing editor for T: The New York Times Style Magazine and has written for The New Yorker, The Wall Street Journal, Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar, and the Financial Times in London. She lives in Paris.

Dana Thomas is the author of the New York Times bestseller Deluxe: How Luxury Lost Its Luster. She began her career writing for the “Style” section ofThe Washington Post, and for fifteen years she served as the European cultural and fashion correspondent forNewsweek in Paris. She is currently a contributing editor for T: The New York Times Style Magazine and has written forThe New Yorker, The Wall Street Journal, Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar, and theFinancial Times in London. She lives in Paris.

Auszug. © Genehmigter Nachdruck. Alle Rechte vorbehalten.

Tangier is a city as ancient as the gods, the point where Europe and Africa meet, where the Atlantic and the Mediterranean kiss. It is a labyrinth of narrow streets “thronged with the phantoms of forgotten ages,” Mark Twain wrote in 1869, and “a basin that holds you,” Truman Capote observed, where “the days slide by less noticed than foam in a waterfall.”

In the early 1960s, a young boy from Gibraltar named John Charles Galliano passed through Tangier by ferry with his Spanish mother, Anita, on his way to and from school in Spain—an exotic commute made necessary by a long-standing diplomatic feud between his father’s homeland and his mother’s. Galliano delighted in their stopovers in this strange, curious place. “The souks, the markets, woven fabrics, the carpets, the smells, the herbs, the Mediterranean color,” he reflected years later. This, he mused, was “where my love of textiles comes from.”

Galliano was born on November 28, 1960, the middle child of three; sister Rose Marie was five years older, and Maria Inmaculada, three years younger. His father, John Joseph, was a plumber who “came from a long line of rather serious and practical men, such as tailors and carpenters, all of whom traditionally began to earn a living from the age of fourteen,” he said.

His mother, Ana Guillén Rueda—known as Anita—hailed from La Línea de la Concepción, the Spanish town across the border from Gibraltar. The Guillén family had long lived in the rural farming region next to the British territory. “They were renowned for their passion for flamenco and a temperament that was utterly fiery and wild,” Galliano said. She grew up under Spanish dictator General Franco’s totalitarian regime—a pro-nationalist and ultra-Catholic society where anti-Semitism flourished. After she married and moved to Gibraltar, she maintained close ties to her homeland, and made sure her young son was educated in the same culture as she had been.

The Galliano family resided at 13, Serfaty’s Passage, a small lane named for the local Jewish population, where the Esnoga Grande, Gibraltar’s principal synagogue, has been located since the early eighteenth century. Gibraltar has had an uneasy relationship with the Jewish community for centuries. Following their expulsion from Spain in 1492, much of the Spanish Jewish diaspora—known as the Sephardim, after the Hebrew word for Spain—passed through Gibraltar on their way to settlements in North Africa. They were given the right to a permanent settlement in 1749 and the population flourished quietly until World War II, when all its residents were evacuated from the two-and-a-half-square-mile territory.

The Gallianos were devout Catholics who attended mass regularly. Galliano was baptized at the Cathedral of St. Mary the Crowned, the baroque seat of the Roman Catholic diocese of Gibraltar, before the same altar where his parents wed. He adored growing up in Gibraltar, mesmerized, he said, by the “bright alleyways, sunshine, blue skies and a main street bustling with sailors.”

But John Joseph wanted more for his children: in 1967, he moved the family to South London, so six-year-old Galliano and his sisters could receive a better education. Galliano remembered thinking how brave his mother was “to depart with three young children to a completely foreign country where she did not speak a word of the language.” They eventually settled in the middle-class neighborhood of Peckham, where they lived in a tan brick Victorian row house at 128, Underhill Road.

London was in the throes of the Swinging Sixties, when the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, and other British Invasion bands were topping the pop music charts; fashion designer Mary Quant was liberating women with the miniskirt and hot pants; film directors Tony Richardson and Richard Lester were turning out cool, ironic comedies like The Knack . . . and How to Get It; and photographers David Bailey, Terence Donovan, and Harry Benson were capturing it all for Harper’s Bazaar, Vogue, and Life. “In a decade dominated by youth,” Time magazine pronounced in its landmark cover story on the city’s cultural renaissance, “London has burst into bloom. It swings; it is the scene.”

The Galliano family wanted no part of that London. Instead Anita, a striking redhead with an olive complexion and a good figure, did what she could to keep the scents, the colors, and the music of southern Spain alive in cold, gray, rainy England. She cooked traditional Mediterranean meals and encouraged her young son to sing—he had a lovely, pitch-perfect voice—and to dance the flamenco. “On tabletops,” he later explained, because “it makes more noise.”

“I knew pretty soon that I had inherited this whole Spanish pride thing from my mother—the way you look and the way you walk and dress,” he admitted. “I never knew anyone with more outfits than her. She was the sort of woman who would dress herself and her children up to the nines and scrub us all with baby perfume until we sparkled just to go out down the road for a coffee. I can still remember all the heads turning as she walked by.”

John Joseph—a fairly short and stocky, fair-skinned, balding man—ran his own plumbing business, and taught his son some of the basics, like how to use a blowtorch. “I would sometimes go out with him on jobs and I was struck by how he always had to have the most perfect finish and the cleanest joint, and how sad it was that all that craftsmanship would never be appreciated,” Galliano said. His father’s profession—which was very low on the English class scale—eventually became a sore spot for him: “People are always talking about how I am a plumber’s son,” he complained. “I am my father’s son primarily. What he chose to do as a career was his choice and he did it very, very well.” Galliano’s mother worked as “dinner lady” in a local school cafeteria. He never made mention of it publicly.

Throughout the home there were souvenirs of their pre-London life, such as a Spanish fan and pictures of Gibraltar. Galliano spoke Spanish with his mother and English with his father. “Other boys’ houses always seemed to smell of dogs and musty carpets,” he said, “whereas ours smelt of garlic and clean laundry and fresh flowers.”

As in Gibraltar, the Galliano family attended mass regularly. On some Sundays, Galliano would serve as an altar boy at the 9:30 service and play guitar for the Latin mass. He was particularly captivated by “all the pomp and ceremony, the clouds of incense, the Holy Communion outfits,” he recalled—an infatuation that would later surface in his fashion shows. For his first communion, he said, “I arrived in this dazzling white suit, bedecked with rosary beads and gold chains and ribbons with all the saints on.” The other boys were in their conservative school uniforms. “I knew I was different,” he admitted, “and I ended up being photographed with all the girls. But it didn’t bother me. I always liked being with the girls, and I also liked looking cool.”

Galliano readily allows that his parents instilled a strong set of values, “like the need for discipline and honesty, the notion that things were only worth doing if you did them to the best of your ability, and the importance of a...

„Über diesen Titel“ kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Weitere beliebte Ausgaben desselben Titels

Suchergebnisse für Gods and Kings: The Rise and Fall of Alexander McQueen...

Gods and Kings: The Rise and Fall of Alexander McQueen and John Galliano

Anbieter: Zoom Books East, Glendale Heights, IL, USA

Zustand: very_good. Book is in very good condition and may include minimal underlining highlighting. The book can also include "From the library of" labels. May not contain miscellaneous items toys, dvds, etc. . We offer 100% money back guarantee and 24 7 customer service. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers ZEV.1594204942.VG

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Gods and Kings: The Rise and Fall of Alexander McQueen and John Galliano

Anbieter: HPB-Ruby, Dallas, TX, USA

Hardcover. Zustand: Very Good. Connecting readers with great books since 1972! Used books may not include companion materials, and may have some shelf wear or limited writing. We ship orders daily and Customer Service is our top priority! Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers S_461841728

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Gods and Kings: The Rise and Fall of Alexander McQueen and John Galliano

Anbieter: Books From California, Simi Valley, CA, USA

Hardcover. Zustand: Very Good. Zustand des Schutzumschlags: Includes dust jacket. Signed. First Edition. Dust Jacket is in a removable clear plastic (Brodart) protector. Signed, in Brodart plastic. First edition. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers mon0003767177

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Gods and Kings : The Rise and Fall of Alexander McQueen and John Galliano

Anbieter: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, USA

Zustand: Very Good. Former library copy. Pages intact with possible writing/highlighting. Binding strong with minor wear. Dust jackets/supplements may not be included. Includes library markings. Stock photo provided. Product includes identifying sticker. Better World Books: Buy Books. Do Good. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers 4638840-6

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Gods and Kings: The Rise and Fall of Alexander McQueen and John Galliano

Anbieter: Bookman Orange, Orange, CA, USA

hardcover. Zustand: Very Good. Zustand des Schutzumschlags: Very Good. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers 2008956

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Gods and Kings: The Rise and Fall of Alexander McQueen and John Galliano

Anbieter: Jackson Street Booksellers, Omaha, NE, USA

Hardcover. Zustand: Fine. Zustand des Schutzumschlags: Fine. 1st Edition. Fine copy in hardcover with fine jacket. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers 040679

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Gods and Kings The Rise and Fall of Alexander McQueen and John Galliano

Anbieter: Haymes Bookdealers, Kingscliff, NSW, Australien

Hardcover. Zustand: Fine. Zustand des Schutzumschlags: Fine. First Edition. Fore edge lightly foxed; Inscribed and signed by the author; 6.56 X 1.31 X 9.56 inches; 432 pages; Signed by Author. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers B4584

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand von Australien nach USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Gods and Kings: The Rise and Fall of Alexander McQueen and John Galliano

Anbieter: YESIBOOKSTORE, MIAMI, FL, USA

hardcover. Zustand: As New. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers 1594204942-VB

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar