Inhaltsangabe

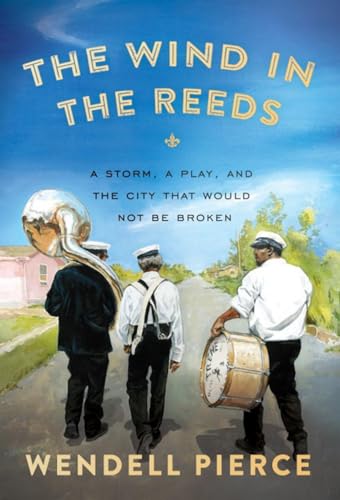

From acclaimed actor and producer Wendell Pierce, an insightful and poignant portrait of family, New Orleans and the transforming power of art.

On the morning of August 29, 2005, Hurricane Katrina barreled into New Orleans, devastating many of the city's neighborhoods, including Pontchartrain Park, the home of Wendell Pierce's family and the first African American middle-class subdivision in New Orleans. The hurricane breached many of the city's levees, and the resulting flooding submerged Pontchartrain Park under as much as 20 feet of water. Katrina left New Orleans later that day, but for the next three days the water kept relentlessly gushing into the city, plunging eighty percent of New Orleans under water. Nearly 1,500 people were killed. Half the houses in the city had four feet of water in them--or more. There was no electricity or clean water in the city; looting and the breakdown of civil order soon followed. Tens of thousands of New Orleanians were stranded in the city, with no way out; many more evacuees were displaced, with no way back in.

Pierce and his family were some of the lucky ones: They survived and were able to ride out the storm at a relative's house 70 miles away. When they were finally allowed to return, they found their family home in tatters, their neighborhood decimated. Heartbroken but resilient, Pierce vowed to help rebuild, and not just his family's home, but all of Pontchartrain Park.

In this powerful and redemptive narrative, Pierce brings together the stories of his family, his city, and his history, why they are all worth saving and the critical importance art played in reuniting and revitalizing this unique American city.

Die Inhaltsangabe kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Über die Autorin bzw. den Autor

Wendell Pierce was born in New Orleans and is an actor and Tony Award-winning producer. He starred in all five seasons of the acclaimed HBO dramaThe Wire and was nominated for an NAACP Image Award for Outstanding Supporting Actor in a Drama Series for the role. He also starred in the HBO seriesTreme and has appeared in many feature films including Selma, Ray,Waiting to Exhale and Hackers. Since Hurricane Katrina, Pierce has been helping to rebuild the flood-ravaged Pontchartrain Park neighborhood in New Orleans.

Rod Dreher has been a writer, columnist and critic for a variety of publications, includingNational Review, The Wall Street Journal, and the Dallas Morning News. He is the author ofCrunchy Cons and The Little Way of Ruthie Leming.

Auszug. © Genehmigter Nachdruck. Alle Rechte vorbehalten.

ONE

A SONG OF RESURRECTION

I drove east across the Claiborne Avenue bridge on the first Friday night in November 2007, two years after the storm that devastated this city. My hometown. My New Orleans. As I came upon the Lower Ninth Ward, there was an extraordinary amount of traffic headed in the same direction as me. They’re coming to see the play, I thought.

The play was Waiting for Godot, Samuel Beckett’s immortal absurdist drama about two tramps, Vladimir and Estragon, living in a wasteland and waiting for a savior who may or may not come. The play, which Beckett wrote inspired by the agonies of Nazi-controlled Paris, deals with abandonment and the struggle inside all of us between hope and despair.

Paris had the Nazi occupation; New Orleans had Hurricane Katrina. We New Orleanians knew abandonment. We knew what it was like to struggle for a lifeline of hope in the midst of a maelstrom of despair. God knows that we who had to deal with FEMA (the Federal Emergency Management Agency) knew absurdity.

Nobody in the city knew it more intensely than the people of the Lower Ninth Ward.

For a long time after the storm, if you drove over the Claiborne Avenue bridge into the neighborhood, you plunged into a void, both physical and existential. There was nothing but a sea of night where once a thriving neighborhood had been. It was the abyss, a black hole of death and desolation, and a darkness so intense that many in New Orleans feared no light could ever overcome it.

On the morning of August 29, 2005, Katrina gashed the levee in two places north of the bridge, which traverses the Industrial Canal, the economically vital artery for shipping from the Mississippi River to Lake Pontchartrain and, via two other man-made canals, out into the Gulf of Mexico. Millions of gallons of water washed through the Lower Ninth Ward, scores of houses were toppled from their concrete pillars. A barge barreled over or through the levee, nobody can say for sure, crushing houses and cars. Hundreds of people drowned as the twenty-foot wall of water flattened everything in its path. It was biblical.

In a single morning, a historic African American neighborhood of fourteen thousand souls, among them the city’s poorest, ceased to exist. Gone were the places where people lived, worked, shopped, prayed, visited, loved. Days later, after the water receded, there was nothing left but ruins, and corpses. In the heat and moisture of south Louisiana, weeds, vines, and trees rapidly consumed the desolate lots and sidewalks. Rattlesnakes and cottonmouths moved in, chasing the rats that overran backyards where children once played and stoops where families used to barbecue. Sometimes, packs of wild dogs owned the streets. The few residents able to return not only had to fight nature just to hold their ground, but also lived in fear of predatory rapists and other savages lurking in the rotting ruins and dark thickets that used to be a neighborhood.

This happened in one of the great American cities, or what was left of it. I knew intimately the agony of the people of the Lower Ninth Ward. Six miles north of the neighborhood, where the Industrial Canal meets the lake, the district of the city where I grew up—Pontchartrain Park, the first African American middle-class subdivision in New Orleans—had been virtually annihilated when a breach in a different canal to the west caused the neighborhood to fill with water up to the rooftops.

Built in the mid-1950s as the wall of segregation was beginning to crack, Pontchartrain Park symbolized the opening of the American dream to black folks in New Orleans—people like Althea and Amos Pierce, my schoolteacher mother and my photographer father, who in 1955 bought a modest ranch home there and started a family. Like their neighbors, Daddy and Tee, as we called our mother, lost everything in the flood. Like so many New Orleanians, from the upscale white enclave of Lakeview to the hardscrabble black Lower Ninth Ward, Daddy and Tee washed up on solid ground far from home, mourning and weeping in their Baton Rouge refuge, wondering if they would ever make it back.

The world post-Katrina was a hard time for my city. The hardest time. For people who didn’t live through it, no words can fully express the pain, the rage, the grief, and the futility we New Orleanians felt. For the people who did, words seemed like a feeble protest against a relentless night without end.

How do you go on when you are bone-tired and broken down by a world where nothing makes sense, and there’s no direction forward that leads to anywhere but the ditch or the grave? How do you embrace a life in which everything and everyone you knew and loved has been taken away, and may never return—and nobody else cares? How do you live through today when you fear there’s no tomorrow?

These are the questions Waiting for Godot explores. In 2006, New York visual artist and publisher Paul Chan visited New Orleans, and when he saw the catastrophic ruin of the Lower Ninth Ward, he thought of Godot and conceived of staging the play for free in one of the neighborhoods most damaged by the ravages of Katrina. A year later, I played Vladimir in the Classical Theatre of Harlem’s New York production of the Beckett play, one that Chan eventually brought to the Crescent City. We did two performances on an intersection near vacant Lower Ninth Ward street corners covered by grass and weeds as high as a man’s chest. We did two more in the Gentilly neighborhood, which, like 80 percent of the city, had also taken cruel licks from the flood.

That night—November 2, 2007—was the first performance. More than six hundred people came and, before the show, ate free gumbo ladled out at the door. When showtime arrived, the Rebirth Brass Band burst into song and led the audience into the bleachers under the floodlights in a classic New Orleans second-line parade. From two blocks away, J. Kyle Manzay, who played Estragon, and I stood in our thrift-store suits and shabby bowler hats, preparing for our entrance. From where we stood, the butt-shaking fanfare of the brass band and the rustle of the crowd taking its seats were the only signs of life in the great and oppressive silence that surrounded us. As close as the people were, it felt like they were a hallucination.

Robert Green, a Lower Ninth Ward resident who lost his mother and granddaughter in the flood, stood in the performance space near the very spot of their death and gave a solemn benediction. On this night, he said, Let’s remember them. Let’s remember all of them.

I did. We all did.

(When we repeated the Godot performance in the Gentilly neighborhood later that month, my mother gave the first night’s benediction as I stood inside an abandoned house, waiting to enter. She ended with “Now, enjoy my son.”)

By then, I could see the audience under the lights. There were people from all walks of life—longshoremen and lawyers, teachers and shopkeepers. People from the neighborhood and people who had never set foot there before that night. All of these people—my people, New Orleanians—gathered in the ruins, expecting . . . what? Comfort? Remembrance? Catharsis? Revelation?

I stood there in the shadows, watching, trying to penetrate the thick canopy of night. There were no houses around us; they’d all been washed away. There were only grassy knolls, weed-choked lots, concrete stumps like teeth in a half-buried jawbone, and matching concrete staircases leading to nowhere.

And there we were, two actors in the center of the darkness, not much more than a stone’s throw from where the levee broke, about to walk forward, poor as we were in the face of so...

„Über diesen Titel“ kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Weitere beliebte Ausgaben desselben Titels

Suchergebnisse für The Wind in the Reeds: A Storm, a Play, and the City...

The Wind in the Reeds: A Storm, A Play, and the City That Would Not Be Broken

Anbieter: Greenworld Books, Arlington, TX, USA

Zustand: good. Fast Free Shipping â" Good condition book with a firm cover and clean, readable pages. Shows normal use, including some light wear or limited notes highlighting, yet remains a dependable copy overall. Supplemental items like CDs or access codes may not be included. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers GWV.1594633231.G

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

The Wind in the Reeds: A Storm, A Play, and the City That Would Not Be Broken

Anbieter: ZBK Books, Carlstadt, NJ, USA

Zustand: good. Fast & Free Shipping â" Good condition with a solid cover and clean pages. Shows normal signs of use such as light wear or a few marks highlighting, but overall a well-maintained copy ready to enjoy. Supplemental items like CDs or access codes may not be included. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers ZWV.1594633231.G

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

The Wind in the Reeds : A Storm and the City That Would Not Be Broken

Anbieter: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, USA

Zustand: Good. Former library copy. Pages intact with minimal writing/highlighting. The binding may be loose and creased. Dust jackets/supplements are not included. Includes library markings. Stock photo provided. Product includes identifying sticker. Better World Books: Buy Books. Do Good. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers 11270749-6

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

The Wind in the Reeds : A Storm and the City That Would Not Be Broken

Anbieter: Better World Books: West, Reno, NV, USA

Zustand: Very Good. Former library copy. Pages intact with possible writing/highlighting. Binding strong with minor wear. Dust jackets/supplements may not be included. Includes library markings. Stock photo provided. Product includes identifying sticker. Better World Books: Buy Books. Do Good. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers 11316733-75

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

The Wind in the Reeds : A Storm and the City That Would Not Be Broken

Anbieter: Better World Books: West, Reno, NV, USA

Zustand: Good. Former library copy. Pages intact with minimal writing/highlighting. The binding may be loose and creased. Dust jackets/supplements are not included. Includes library markings. Stock photo provided. Product includes identifying sticker. Better World Books: Buy Books. Do Good. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers 11270749-6

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

The Wind in the Reeds: A Storm, A Play, and the City That Would Not Be Broken

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Atlanta, AUSTELL, GA, USA

Hardcover. Zustand: Very Good. No Jacket. May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers G1594633231I4N00

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

The Wind in the Reeds: A Storm, A Play, and the City That Would Not Be Broken

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Atlanta, AUSTELL, GA, USA

Hardcover. Zustand: Very Good. No Jacket. Missing dust jacket; May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers G1594633231I4N01

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

The Wind in the Reeds: A Storm, A Play, and the City That Would Not Be Broken

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Dallas, Dallas, TX, USA

Hardcover. Zustand: Very Good. No Jacket. Former library book; May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers G1594633231I4N10

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

The Wind in the Reeds: A Storm, A Play, and the City That Would Not Be Broken

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Reno, Reno, NV, USA

Hardcover. Zustand: Very Good. No Jacket. May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers G1594633231I4N00

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

The Wind in the Reeds: A Storm, A Play, and the City That Would Not Be Broken

Anbieter: ThriftBooks-Dallas, Dallas, TX, USA

Hardcover. Zustand: Very Good. No Jacket. May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers G1594633231I4N00

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar