Inhaltsangabe

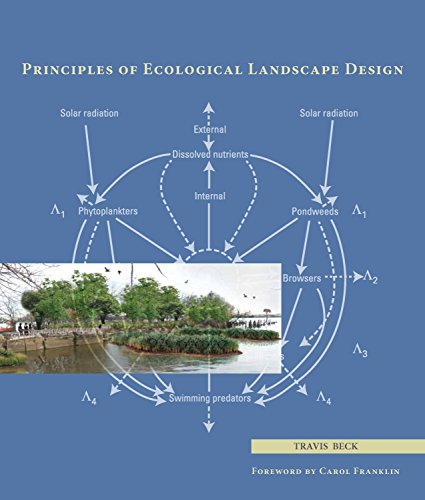

<div></div><p>Today, there is a growing demand for designed landscapes—from public parks to backyards—to be not only beautiful and functional, but also sustainable. With <i>Principles of Ecological Landscape Design</i>, Travis Beck gives professionals and students the first book to translate the science of ecology into design practice. <br><br>This groundbreaking work explains key ecological concepts and their application to the design and management of sustainable landscapes. It covers topics from biogeography and plant selection to global change. Beck draws on real world cases where professionals have put ecological principles to use in the built landscape. <p></p></p><br>For constructed landscapes to perform as we need them to, we must get their underlying ecology right. <i>Principles of Ecological Landscape Design </i>provides the tools to do just that.<br><br>

Die Inhaltsangabe kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Über die Autorin bzw. den Autor

Auszug. © Genehmigter Nachdruck. Alle Rechte vorbehalten.

Principles of Ecological Landscape Design

By Travis BeckISLAND PRESS

All rights reserved.

Contents

Acknowledgments,

Foreword,

Introduction,

1 Right Plant, Right Place: Biogeography and Plant Selection,

2 Beyond Massing: Working with Plant Populations and Communities,

3 The Struggle for Coexistence: On Competition and Assembling Tight Communities,

4 Complex Creations: Designing and Managing Ecosystems,

5 Maintaining the World as We Know It: Biodiversity for High-Functioning Landscapes,

6 The Stuff of Life: Promoting Living Soils and Healthy Waters,

7 The Birds and the Bees: Integrating Other Organisms,

8 When Lightning Strikes: Counting on Disturbance, Planning for Succession,

9 An Ever-Shifting Mosaic: Landscape Ecology Applied,

10 No Time Like the Present: Creating Landscapes for an Era of Global Change,

Bibliography,

Index,

CHAPTER 1

Right Plant, Right Place: Biogeography and Plant Selection

It is often said that the secret to good horticulture is putting the right plant in the right place. By matching plants to their intended environment, a designer helps to ensure that the plants will be healthy, grow well, and need a minimum of care. Too often designers force plants into the wrong places, putting large trees that thrive in extensive floodplains into confining tree pits or planting roses that need full sun in spindliness-inducing shade. Or we try to create a generically "perfect" garden environment, with rich soils and regular moisture, for a wide-ranging collection of plants, some of which may actually prefer more stringent conditions. Whether we do these things from ignorance, in conformance with established practices, or because our focus is on aesthetic qualities or our associations with certain plants, the too common result is struggling plantings, ongoing horticultural effort, and the dominance of familiar generalist species.

An ecological approach to landscape design takes the fundamental horticultural precept—right plant, right place—and views it through a biogeographical lens. Where do plants grow, and why do they grow there? How many degrees of native are there? What are the relative roles of environmental adaptation and historical accident? Selecting plants according to biogeographical principles can help us create designed landscapes that will thrive and sustain themselves. Such landscapes celebrate their region and fit coherently into the larger environment. Of course, these landscapes can also be beautiful. Let us begin, then, with a fundamental ecological question: Why is this plant growing here?

PLANTS ARE ADAPTED TO DIFFERENT ENVIRONMENTS

Five hundred million years ago the earth's landmasses were devoid of life. Then, scientists speculate, ancestral relatives of today's mosses began to grow along moist ocean margins and eventually on land itself. To survive out of water, these primitive plants had to evolve structures to support themselves out of water, ways to avoid drying out, and the ability to tolerate a broader range of temperatures. As they evolved, plants diversified and spread into every imaginable habitat, from deserts to wetlands, and from the tropics to the Arctic. Today, there are more than 300,000 plant species on our planet (May 2000).

Plant diversity and the diversity of habitats on Earth are closely related. Natural landscapes are composed of heterogeneous patches, each of which presents a different environment (see chap. 9). At the largest scale are deserts and rainforests. At the smallest scale are warm, sunny spots and wet depressions. Charles Darwin proposed in The Origin of Species(1859: 145),

The more diversified the descendants from any one species become in structure, constitution, and habits, by so much will they be better enabled to seize on many and widely diversified places in the polity of nature, and so be enabled to increase in numbers.

Plants have been able to move into so many different environments because they have developed many means of adapting. Consider plant adaptations to two critical environmental variables: temperature and the availability of water.

Temperature affects nearly all plant processes, including photosynthesis, respiration, transpiration, and growth. Very high temperatures can disrupt metabolism and denature proteins. Low temperatures can reduce photosynthesis and growth to perilously low levels and damage plant tissues as ice forms within and between cells. Plants that grow in high-temperature regions may have reflective leaves or leaves that orient themselves parallel to the sun's rays in order to not build up heat. Some use the alternate C4 photosynthetic pathway, which can continue to operate efficiently at high temperatures. Plants in cold regions have developed bud dormancy and may grow slowly over several seasons before producing seed. They have high concentrations of soluble sugars in their cells to act as natural antifreeze, and they are able to accommodate intercellular ice without experiencing damage.

Plants that are adapted to grow well in wet, moist, and dry conditions are called, respectively, hydrophytes, mesophytes, and xerophytes. Hydrophytes have to provide oxygen to their flooded roots, which they do through a variety of mechanisms, including by developing spongy, air-filled tissue between the stems and the roots or by growing structures like knees that bring oxygen directly to the roots (fig. 1.1). Many hydrophytes also have narrow, flexible leaves to avoid damage from moving water. Xerophytes, on the other hand, exhibit adaptations to lack of water such as small leaves, deep roots, water storage in their tissues, and use of an alternate photosynthetic pathway that allows them to open the stomata on their leaves only in the cool of night (fig. 1.2).

Because of 500 million years of evolution and the diversity of habitats open to colonization, the planet is now filled with plants adapted to nearly every combination of environmental variables.

CHOOSE PLANTS THAT ARE ADAPTED TO THE LOCAL ENVIRONMENT

Because plants exhibit such a wide range of natural adaptations, we need not struggle—expending both limited resources and our collective energy—against the environment we find ourselves in to make it a better home for ill-suited plants. Using biogeography as our guide, we can always identify plants ready-made for the conditions at hand.

Gardeners, nursery owners, and landscape designers have long recognized that plants ill-suited to the temperature extremes of the place where they are planted are unlikely to survive their first year in the ground. The US Department of Agriculture has codified this knowledge in a map of hardiness zones, which was updated in 2012 (fig. 1.3). Hardiness zones represent the average annual minimum temperature, that is, the coldest temperature a plant in that zone could expect to experience. There are thirteen hardiness zones, ranging from zone one in the interior of Alaska (experiencing staggering winter minimums of below –50°F) to zone thirteen on Puerto Rico (experiencing winter minimums of barely 60°F). Plants are rated as to the lowest zone in which they can survive. Balsam fir (Abies balsamea), for instance, is hardy to zone three. The hardiest species of Bougainvillea are hardy only to zone nine. Plants are sometimes given a range (e.g., zones three to six). Strictly speaking, hardiness refers only to ability to survive...

„Über diesen Titel“ kann sich auf eine andere Ausgabe dieses Titels beziehen.

Weitere beliebte Ausgaben desselben Titels

Suchergebnisse für Principles of Ecological Landscape Design

Principles of Ecological Landscape Design

Anbieter: Books From California, Simi Valley, CA, USA

hardcover. Zustand: Very Good. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers mon0003885417

Gebraucht kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar

Principles of Ecological Landscape Design

Anbieter: GoldBooks, Denver, CO, USA

Zustand: new. Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers 97D71_53_1597267015

Neu kaufen

Versand innerhalb von USA

Anzahl: 1 verfügbar