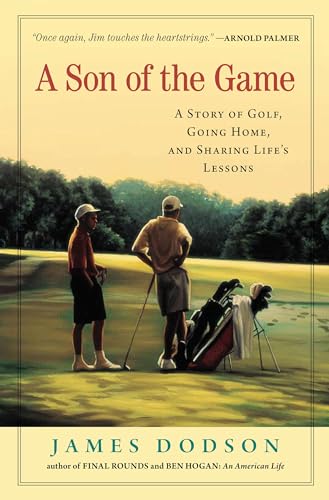

When acclaimed golf writer James Dodson leaves his home in Maine to revisit Pinehurst, North Carolina, where his father first taught him the game that would shape his life and career, he’s at a point where he has lost direction. But once there, the curative power of the sandhills region not only helps him find a new career working for the local paper but also reignites his flagging passion for the game of golf. And, perhaps more significantly, it inspires him to try to pass along to his teenage son the same sense of joy and contentment he has found in the game, and to recall the many colorful and lifelong friends he has met on the links.

This wise memoir about finding new meaning through an old sport is filled with anecdotes about the history of the game and of Pinehurst, the home of American golf, where many larger-than-life legends played some of their greatest rounds. Dodson's bestselling memoir Final Rounds began in Pinehurst twenty-five years ago, and now A Son of the Game completes the circle as it follows his journey of discovery back to where his love of the game began—a love that he hopes to make a family legacy.

A Son of the Game

By JAMES DODSONAlgonquin Books of Chapel Hill

Copyright © 2009 James Dodson

All right reserved.ISBN: 978-1-56512-506-3Chapter One

Pants That Just Say Pinehurst

At the end of Spring 2005, on my way to cover the 105th United States Open Championship at Pinehurst, I stopped off to buy a new pair of pants.

I realize how unexciting this sounds, but buying new pants is a rare event for me, something I do about as frequently as Americans go to the polls to elect a new president, which may explain why my pants, always tan cotton khakis, look as if they've seen better days.

In this instance, it was a perfect Sunday afternoon, twelve days before the start of our national golfing championship, and I'd just rolled into Pinehurst following a long drive from Maine.

Actually, when I arrived, I had no intention of buying pants. I was mostly worrying about locating the small log cottage in the middle of Southern Pines that I'd rented sight unseen via telephone from a local realtor named Ed Rhodes, who casually informed me the key would be waiting beneath a stone angel by the back door. I was also vaguely wondering if I'd made the dumbest career move of my life by agreeing to go to work for the Southern Pines Pilot, the award-winning community newspaper of the Carolina Sandhills.

Some guys, when facing a midlife crisis, roguishly splurge on a red sports car, or get hair plugs, or maybe even buy a secret condo in Cancn. Fresh from a year in which I'd traveled to Africa with exotic plant hunters and loitered at the elbows of some of the world's top horticulture experts, I'd merely yielded to the persuasive charms of The Pilot's enthusiastic young publisher, David Woronoff, scion of a distinguished Old North State newspaper clan. Almost on a whim, I'd agreed to write a daily golf column for the paper's ambitious Open Daily tabloid during U.S. Open week. There was also a friendly conversation about the possibility of my staying on to write a Sunday essay after the Open circus left town, though nothing had been formally proposed, much less agreed upon. That wasn't by accident.

Truthfully, I feared that I had little in the way of wit or current insight to offer The Pilot and its Open readers because, factoring in the four long years my brain had been focused upon the distant, well-ordered world of Ben Hogan and another kind of America, and adding two years for my absorbing romp through the garden world, I'd been out of the current game for a small eternity. Since the death of Harvie Ward and the dissolution of my longtime golf group back in Maine, in fact, I'd scarcely touched my own clubs or watched a golf tournament on television or even felt much desire to read about who was doing what in a game I'd loved, it seemed, forever.

Like some sad, burned-out bureaucrat from a Graham Greene novel, I'd even begun to consider the once-unthinkable possibility that my hiatus from golf and the golf world, rather than rekindling my desire to play and restoring interest in the professional game as well, had radically cooled my passion and turned my game to sawdust.

This realization had come during the drive, when I'd stopped off to compete with a friend named Howdy Giles in his one-day member-guest event at Pine Valley Golf Club in New Jersey. Though Pine Valley is justly famous for its strategic brilliance and difficulty, I often play the course surprisingly well for a casual player, typically managing to achieve my five- or six-stroke handicap. In this instance, I thought my lengthy time away from the game might even serve to boost my prospects of making a decent score - partly because I tend to play better golf on a difficult course and partly because some of my best rounds of golf have come following the long winter layoffs every New Englander comes to know.

Well, the golf gods must have needed a good belly laugh that day. By the fourth hole, I was six over par, and by the end of the first nine, I'd jotted a big fat fifty on the card - probably my worst competitive nine holes in forty years. The anger and embarrassment I felt made me want to grab my clubs and bolt.

"Don't worry about it," my genial host assured me at the halfway house, as I licked my wounds, guzzled Arnold Palmer iced tea, and wondered if perhaps I was through with golf or, more likely, if golf was through with me. "You'll put it together on the back nine," Howdy confidently said. I wasn't so sure.

Fortunately, Howdy was right. I shot a not-quite-so-horrific forty-five. As I left the grounds of the world's number-one-ranked golf course, my cell phone rang. It was my son Jack calling, curious to know how the old man had fared that afternoon. Originally Jack had planned to accompany me to Pinehurst to work as a standard-bearer with his friend Bryan Stewart at the U.S. Open. But late spring snows in Maine had extended his freshman-year high school classes all the way to the start of Open week. There was still an outside chance he might fly down on Tuesday of that week, however, and find a spot working in the National Open. This was my great hope, anyway. I wanted the time with my son, and I also felt the experience would be invaluable for him.

"Let's just say I left the course record more or less intact." I attempted to shrug off the disaster, fessing up to my woeful ninety-five.

"Gosh, what happened?" Jack sounded genuinely astounded and also a little disappointed. After all, one of the carrots I'd long held out to him was a promise to play shrines like Pine Valley, Pebble Beach, and Pinehurst No. 2 if and when his game reached a level those courses demanded. "Pine Valley must be really hard," he said.

"It is hard, Nibs. Make no mistake. But truthfully I was just awful today. I hit every kind of bad shot you can - hooks, shanks, even a whiff. I five-putted a hole from twenty feet."

"Maybe you should have played a little more before you went there," he said, politely stating the obvious.

"You're right. I should have," I agreed, wondering if the lengthy hiatus had done more serious damage to my game than I realized.

Despite my misgivings, David seemed to have no doubts about why he wanted me to work for The Pilot.

"Between you and me," David had confided at lunch in a crowded caf overlooking Southern Pines' picturesque main street the morning after I said goodbye to Harvie, "we're eager to show the national media that Pinehurst is our golf turf, not theirs. We'd like you to help us do that."

David explained that during the 1999 Open at Pinehurst, The Pilot had broken new ground by being the first to publish a comprehensive, full-color daily tabloid newspaper, fifty-six pages in length, for the two hundred thousand spectators who attended the Open, a publishing feat for which Woronoff and his staff had collected a pile of industry awards. Now, he said, for the 2005 Open, they were out to reprise their effort and in the process double the output in pages and increase market penetration.

"This is where you come in," he said, sipping his iced tea. "I took a poll, phoned everybody I could think of in the golf world, and asked the same question: If I could get one nationally known golf writer to come write exclusively for us for the Open, who should I try to get? Your name kept coming up. I know we can't possibly pay you what the national media guys do. But on the other hand, I've read your books and know from Tom Stewart and others how connected you are to the Sandhills."

"This is where I...