Beschreibung

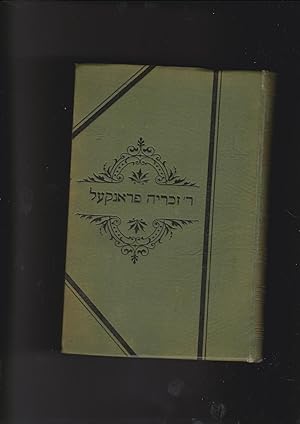

[1], 351, [9], III-VIII pages. 203 x 140 mm. Frankel was a Bohemian-German rabbi and a historian who studied the historical development of Judaism. Frankel was the founder and the most eminent member of the school of historical Judaism, which advocates freedom of research, while upholding the authority of traditional Jewish belief and practice. This school of thought was the intellectual progenitor of Conservative Judaism. Frankel was, through his father, a descendant of Vienna exiles of 1670 and of the famous rabbinical Spira family, while on his mother's side he descended from the Fischel family, which has given to the community of Prague a number of distinguished Talmudists. He received his early Jewish education at the yeshiva of Bezalel Ronsburg (Daniel Rosenbaum). In 1825 he went to Budapest, where he prepared himself for the university, from which he graduated in 1831. In the following year he was appointed district rabbi ("Kreisrabbiner") of Litomerice by the government, being the first rabbi in Bohemia with a modern education. He made Teplice his seat, where the congregation, the largest in the district, had elected him rabbi. He was called to Dresden in 1836 as chief rabbi, and was confirmed in this position by the Saxon government. In 1843 he was invited to the chief rabbinate at Berlin, which position had been vacant since 1800, but after a long correspondence he declined, chiefly because the Prussian government, in accordance with its fixed policy, refused to officially recognize the office. He remained in Dresden until 1854, when he was called to the presidency of the Breslau seminary, where he remained until his death. Frankel held that reason based on scholarship, and not mere desire on the part of the laity, must be the justification for any reforms within Judaism. In this sense Frankel declared himself when the president of the Teplice congregation expressed the hope that the new rabbi would introduce reforms and do away with the "Missbräuche" (abuses). He stated that he knew of no abuses; and that if there were any, it was not at all the business of the laity to interfere in such matters (Brann, in his "Jahrbuch," 1899, pp. 109 et seq.). He introduced some slight modifications in Jewish prayer services such as: the abrogation of some hymns, the introduction of a choir of boys, and the like. He was opposed to any innovation which was objectionable to Jewish sentiment. In this respect, his denunciation of the action of the "Landesrabbiner" Joseph Hoffmann of Saxe-Meiningen, who permitted Jewish high-school boys to write on the Sabbath, is very significant ("Orient," iii. 398 et seq.). His position in the controversy on the new Hamburg prayer book (1842) displeased both parties; the liberals were dissatisfied because, instead of declaring that their prayer-book was in accord with Jewish tradition, he pointed out inconsistencies from the historical and dogmatic points of view; and the Orthodox were dissatisfied because he declared changes in the traditional ritual permissible (l.c. iii. 352-363, 377-384). A great impression was produced by his letter of 18 July 1845, published in a Frankfurt-am-Main journal, in which he announced his secession from the rabbinical conference then in session in that city. He said that he could not cooperate with a body of rabbis who had passed a resolution declaring the Hebrew language unnecessary for public worship. . . . Bestandsnummer des Verkäufers 008517

Verkäufer kontaktieren

Diesen Artikel melden

![]()